Abstract: More than in the recent past, the socio-political heredity of the long-term presence of Islam in Southeast Europe deserves to be questioned in the light of the today’s climate of suspicion and heightened tensions towards autochthonous Muslim minorities. If the Weber’s term sultanism used to depict the Ottoman rules across the former “European Turkey” has described a counter-narrative with the academic literature, yet the question regarding the passage from a multi-ethnic coexistence to the contemporary deterioration of human relations among the Balkan populations remains open. Because of that, this analysis aims to unravel the main shades of Balkan Islam in order to point out how such collective identity(-ies) has come to represent more a set of rules of social practices than a pristine form of faith. By focusing unheard case-studies within Kosovo, Bosnia Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Albania, the usage of the term “idiosyncratic identity” will serve to turn the prejudices upon Muslim communities into a clear understanding of the political role of Balkan Muslims. Therefore, a further identification of volatile and (trans-)formative form of Islam will come to unmask the today’s “outside construction” and political manipulation that currently impinge on interethnic relations and expose Muslim communities to a wealth of misconceptions, stereotypes and discrimination.

Keywords: sultanism, Balkan Islam, minority groups, identity, manipulation;

In the contemporary climate of suspicion over Muslim communities across Europe, a detailed political and cultural analysis on potential radicalisation of jihadist-oriented groups polarises a dichotomy of opinion between those who consider such religious identity a threat for the public realm and those who insist that Islam per se does not represent a cultural barrier for a sustainable multicultural society. In the past few years, the Balkan region has been one of the most significant European contexts in which external factors, such as the rise of global pro-jihadi ideological organisations (e.g., Islamic State, al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, al-Shabeb), have impinged the Muslims’ identity due to processes of “confessional reconstructions”. Contrary to West Europe where Islam began to intensify tensions after migratory phenomena and military intervention from the post-colonial Africa to Middle East and Central Asia, the Southeast Europe has always been “homeland” for a large number of autochthonous Muslim communities. As Gerald Shenk notes indeed, a history of Islam in Europe cannot overlook the presence of Muslim groups in the Balkans[1] in the attempt to build up a counter-narrative opposite to the intense fear, hatred and negative attitudes towards Islam as a whole.

More than in the recent past, to take a close look at the historical and socio-political development of the Balkan Islam means to try to unravel the Muslims’ identity that in form of minority has affected the majoritarian cultural societies from within. From a historical viewpoint, in Southeast Europe Islam was spread by conquest and not by forcedly imposed conversations on the non-Muslim Balkan populations throughout the long-presence of the Ottoman Empire. As a result, Balkan Muslims have shown an inclination towards Turkey as the only one country of reference to culturally address over the Islamic world and as legitimate heir of the Ottoman heritage, whose revival has aroused increasingly. Thus far, the so-called “European Turkey” began to label all successor States of the Ottoman Empire (e.g., Albania, Bulgaria, Kosovo, Macedonia, partially Southern Serbia) as members of a region where autochthonous groups have firstly acquainted the Islam and kept its legacy after the demise of the Turkish Ottomans.

At a time when analysts and commentators are unsure about Turkey’s pivotal role of “contractor”[2] or of ağabey (e.g., “big brother” in Turkish language) and its future strategy to intervene on behalf of their “Turkic ancestors” to better leverage its journey to EU accession, a valuable contribution on Ankara’s interests and influence over Southeast Europe is again twofold. On the one side, those who consider the “Strategic Depth” elaborated by the former Prime Minister of the Republic of Turkey Ahmet Davutoğlu a win-win instrument to succeed in the journey towards the EU integration. On the other side, those who consider today’s Ankara and Brussels relations into a definitive blockade as a result of the 2016 Turkish coup d’état attempt and ongoing military operations alongside the Turkish-Syrian border. In addition, it remains arguable that Kemalist and Islamic intelligentsia in Turkey would culturally understand the former Ottoman Rumelia as the place of the Turkish transition towards a universal modernity. In between, a higher level of hate speech against Muslim and Turkish communities especially in Bulgaria, and lack of interethnic well-living in contested societies, such as in Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, among others, are currently carving out an anti-Turkey historical narrative and growing sense of Islamophobia. The latter, however, does not seem to be defeated by misleading affirmations alike Davutoğlu’s addressing the Bulgarian Muslims with the proud shriek “Yes, we are the new Ottomans”[3].

Besides, a de-contextualised and not static time analysis on Islamic identity all across the Balkans – with exceptions for Slovenia, Croatia and Romania -, opens up more intriguing questions. Do Balkan Muslims identify themselves with Turkey and the Ottoman heritage because of the Islamic faith? To what extend it is possible to consider Balkan Islam as a historically consequent phenomenon of the Ottoman experience? More importantly, to what kind of manipulations and reinterpretations Balkan Muslims have been exposed throughout regional de-territorialisation?

Similarly to Nicolò Machiavelli, who captured the essence of the Ottoman Empire by describing the “whole Monarchy of the Turks […] governed by one lord [while] the others are his servants”, today’s reference to Islam among Balkan peoples has (unsurprisingly) maintained a negative allusion. Due to the rise of Balkan romantic nationalisms triggered before and after the anti-Ottoman battlegrounds at the end of the nineteen century, the (mis-)/conception regarding Islam began to increase an idea of “religion of the occupants” through real and perceived images of “slaughters”, “slavery” and “poverty”. Historically, such anti-Islam narrative began to take place after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 at first, when the Orthodox Church began its overwhelming campaign in defence of the European bulwark of Christendom and against the “Muslim occupants”. By drawing a divisive remark along Christian and non-Christian communities, Muslim people, mainly Turks, and those locals who forcedly and spontaneously converted to Islam (e.g., Slavs, Vlachos, Albanians and Bulgarians) were recognised as “Turks” even without proper evidence of their ethnicity and belongingness. A widespread anti-Turkic discourse aroused in the sphere of art, literature and politics accordingly, paving the way toward more detailed discussions on the cultural role and political usage of Islam as an instrument of power in the central regions of the Balkans and Anatolia.

In this regards, Max Weber defines the Ottoman Empire as a “curious mixture of modern and patrimonial elements that decayed when they entrenched themselves at the expense of the modern ones”[4]. In his argumentation, Weber tries to smoothly redefine the concept of Ottoman administration by using the term “sultanism” as a neologism to depict a set of strategic rules aimed at keeping control over an extremely extended territory through a narrow maximization of taxation and military state system. Within the Ottoman Empire, indeed, high level of taxation in tandem with a military state system, whose management was entrusted to the sihapi (e.g., Ottoman cavalry corps) and the zaim (e.g., military governor of the land tenure of Empire), were established to pursue financial and strategic advantages from the provinces of the Empire. In few words, both high taxation and compulsory military service were a pure instrument of the master, namely of the Sultan, fully integrated to a reasonably consistent set of rules aimed at guaranteeing a good-neighbourly interethnic relations between Turkish-Ottoman settlers and Balkan locals, i.e., komşu, which literally means “neighbour” in Turkish language. However, the devshirme tax, also well-known as “blood tax”, was a heart-breaking price to pay for non-Muslim families, in time recognised as one of the most repressive instrument of the Turkish Ottoman power against non-Islamic communities.

Despite everything, a conspicuous growth of conversations to Islam were registered throughout the Ottoman administration, mainly in the poorest rural area of the Kosovar millet, in which 70% of ethnic-Albanian dwellers got used to Turkish Ottoman heritage, in Bosnia and Southern Bulgaria. This is why Weber’s “sultanism” seems to correctly describe a political system that allowed pluralism even though strongly centralised, and in the meantime it recalls the Francis Fukuyama’s idea on the power limitations that Ottoman central power faced by allowing confessional laws to pertain to personal and collective cases within each Millet. For instance, whether legal disputes and further trials were conducted in Ottoman courts according to the Sharia law for Muslim residents, equally Orthodox Christian institutions were allowed to apply their judicial standards in a wide range of legal cases, i.e., marriages, inheritance and so forth. Orthodox Patriarchs were indeed officially responsible in front of the Sultan for “their” people’s behaviour within the Millets and even for themselves since they could get married and have children in accordance with the priestly form of nicholaism[5]. Therefore, Weber’s and Fukuyama’s viewpoints strengthen the idea about the lack of direct implication of Islam as a dominant policy for keeping non-Muslim identities at check. Conversations to Islam were likely decided to avoid the payment of taxes as well as for politically oriented interests of non-Muslim élites to which Turkish Ottomans provided dominant positions in their outlying regions, mainly in Albania and Bosnia, in order to balance domestic affairs from within.

Thus, religion – no matter if Islam, Orthodox Christianity, Catholicism, or Judaism -, was only used as a yardstick to identify as individuals as collective groups within the Millet system.

At this point, the Weber’s usage of the term “sultanism” becomes highly arguable in academia. Stefan Pavlowitch associates the concept of millet system with “religion” indeed, instead of using “sultanism” or the common translation related to topography, i.e., “province”, “state” and so forth. In other words, religion per se did not interplay in terms of religious faith, whereas it was a relevant reference of a cultural and social norm of conduct that each millet. Similar to Pavlowitch, the political analyst and expert in Albanian affairs Miranda Vickers remarks that religion was one of the most important factors through which Turkish Ottomans established their concept of governance all across the empire[6]. In general, Islam was neither an imposition of something alien nor an instrument to promote and impose a new branch of religious State whose central power did not square local experiences and different heritages. While Weber’s “sultanism” could serve to understand at least the reasons behind the Ottoman foreign policy and further long-term fiscal distress that weakened the administration prior to its definitive collapse, Islam does not offer a unique paradigm for how Ottoman Empire should be historically recollected. In fact, the Ottoman collapse in Southeast Europe was partially triggered by a series of antisocial behaviourisms and bandit revolts that Turkish-oriented and Islam-converted communities carried out, such as Albanians’. In addition, unpolitical Islam has predominantly challenged the positive quality of social interactions in mixed-religious localities, alike the large Turkish-style bazar of Baščaršija in Sarajevo, in which the identity formation along ethnic lines began within the Yugoslavian regime and brought the latter to implode and ending up in gross violation of human rights and ethnic cleansings.

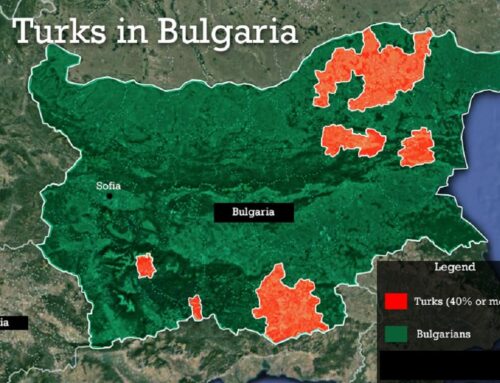

Hence, it becomes even clearer that phenomena of “forced conversations” to Islam were not imposed on non-Muslim communities, and that Islam became part of a cultural and political rivalry between those élites prompt to manipulate collective identities in order to divide and rule in the vacuum left by Turkish Ottomans. For instance, the so-called “Albanian question”, namely the Albanian issue regarding a communitarian claim over a (mother-)/land twice larger than today’s recognized territory of the Republic of Albania, has never come to shape the Albanian religious consciousness. By contrary, a national awareness aroused among ethnic-Albanian peoples and took place on the basis of the sense of ethnic belongingness. The Albanian writer Pasko Vasa, whose call for all “Muslim, Catholic, Orthodox Christian Albanians, no matter where and no matter how many”, remains in the history of Albanian literature, together with his term “Albanism”, which he coined to lay out the religion of Albanians[7] and that gained popularity not only among Albanians. Yet another example, in Bulgaria Islamic identity has always been misleading as it incorporates a mixture of Christian and Pagan elements together with Muslim livelihoods that Muslims have kept together with a Bulgarian-speaking attitude and other folk traditions. In general Bulgarian Muslims have been historically misrecognised as “Turks”, but the artificial attempt of the “Revival Process” (1984-1989) that the last Communist regime set up to force Bulgarian Turks to change names[8] for convincing them to have Bulgarian descendants who had been previously islamised by Turkish Ottomans, has shown the extended degree under which Islam has been threaten. An continuous exposition to political manipulations and confessional reconstructions that have brought the majority of Bulgarian Muslims to currently live into a rocky marginalization and exclusion from the core society, without a sufficient level of education and a decreasing proficiency of Bulgarian language.

After all, Islam per se has never created an oasis of persistence hatred and violence as some continue to portray[9], even though such religious identity has never succeed to build up an oasis of peace, tolerance, and comprehension between different ethnic groups in the Balkans. In this case, whether an overview on the Ottoman Empire brings “what really happened” to light and facilitates analyses on today’s role of Balkan Islam, at issue is the essence of the religious, at whose centre a pure or constructed acts of embodiment tend to involve sub-national and ethnic groups and other groupthink issues. More precisely, since Balkan Islam has historically comprised collective groups that belong neither to Arab nor to Middle Eastern origin, they are exposed to misleading reinterpretations of sacred texts, confessional reconstructions and political manipulations able to trigger perilous changes in the traditional branch of the Balkan Islam, that is, the Islamic Hanafi School. The Ottoman Empire’s vacuum has been constantly replaced by form of practising and teaching arriving from Muslim-majority societies in Middle East, in which Islam remains tightly connected with national, ethic, moral and social values that are foreign to Balkan Muslims. In the past few years, indeed, externally religious reverberations have put “under fire” the traditional form of Islamic practicing in the Balkans, meanwhile weakening their volatile religious identity in a profound and grove identity crisis. This explains the diffusion of jihadi-propaganda of ultra-conservative and transnational religious-political Salafism[10] within Bulgarian Roma groups[11] and the dissemination of Wahabbism in the Bosnian education system aimed at shaping a “new Muslim being”[12].

Within this, the socio-cultural and political role of Islam in Balkan societies is no longer easy to unravel because it tends to be complicated by the fact the Islam is a religion alike those whose sacred scriptures containing passages and practicing that even Muslim believers and experts would consider extremely problematic. Perhaps a look at a bigger picture unravels today’s state of affairs. Instead, such overview poses once again a dichotomy between an “in-group loyalty” within Muslim communities and an “out-group hostility” that manipulates the debate and leads it to catastrophic proportions used by analysts, politicians and anti-Islam movements for describing Islam as a threat for the public realm and potential staging ground for terrorist operations and radical propaganda. In this case, I borrow the theoretical approach of concentric circles through which Maajid Nawas frames the Islamic groups worldwide[13].

In my opinion, in the Balkan region there is at the centre the first circle within those groups that tend to be externally influenced by jihadi-movements, such as Islamic State, al-Qaeda, Boko Haram, al-Shebab and so forth. Their incitements to war and interethnic enmity found a fertile arena after the Balkan Wars in 1990s and recently when ISIS’s attempts to target the Western Balkan Muslims were aimed at turning a pathological hotspot afflicted by painful economic development, injustice, instability and poverty into a “terrorist haven”. Around this, there is another and larger circle in which Muslims are involved in Islam despite they appear less eager to kill on behalf of Allah and willing to be killed for Allah. Within this, Muslims are more oriented to follow and support Islam financially, philosophically, and morally, and concepts such as secularism, democracy and reinterpretation of Qur’an appear an assault upon their collective identity. In other words, they are not inclined to get their hands dirty, but they express their willingness to live their lifeworld in accordance with more modern value than keeping old-fashioned Islamic tradition. Yet, there is a third circle, which is the broadest group and represents those Muslims that “happened to be Muslims”. In my opinion, they are those Muslim autochthonous citizens who identify themselves “as Muslims” because of a set of social practises and moral rules that they traditionally follow in their families, but do not mean a straightforward practising of Islam at the same time. Even though they do not look secular and open-minded, Balkan Muslims of the third group have a very low understanding of Islam and sacred texts of Qur’an as they do not speak fluently Arabic, and thereby potentially exposed to manipulations of charismatic recruiters or ideological dogmas. Unfortunately, they represent the majority of the Balkan Muslims and are involved in today’s campaigns for political and cultural recognition within majoritarian cultural systems (e.g., Bulgaria, Macedonia, Greece) or engaged in processes of policy-making aimed at “sharing religions in order to shape Nations” (e.g., Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo).

In the past few years, this so-called “idiosyncratic identity” of both second and third group has succeed to maintain the Balkan region untangled from a deep Islamist and jihadist intrusion, whose attempts have been truncated by local security in cooperation with international intelligence. However, they remain the most unvoiced and the weakest Muslims over the region, unlike those charismatic recruiters and religious leaders from the smallest and first circle that paradoxically are able to endorse “outside construction” and reinterpretation of Islamic identity(-ies). It follows that unheard position and ghettoization trigger processes of more self-segregation and antisocial behaviours that on behalf of “cultural authenticity” and “cultural protection” bring Muslims to feel a sense of reflexive solidarity with other Muslim brothers and sisters – no matter how barbaric their commitment might be – and satisfy (unconsciously) religious leaders’ aspirations to become community chieftains. In other words, such idiosyncratic identity of Balkan Muslims is nowadays “under fire” due to high level of marginalization and self-isolationist attitudes that seem to facilitate local figures and recruiters eager to get something else out of it, and political groups ready to manipulate their collective identity by imposing new ideologies to believe in. Therefore, this idiosyncrasy could potentially expose Balkan Muslims to endless identity crises affected due to real or perceived grievance narrative of exclusion, such as for the Roma Radicals local case in Bulgaria, and sorrow for post-war scenarios, such as in Bosnia-and-Herzegovina and Kosovo.

To sum up, it would be correct to lay out Balkan Islam as a religious identity within which more minority groups have a different set of rules of social practices, rather than describing it as a pristine and monolithic form of collective with its religious faith. To conclude, while integration policies might disempower potential recruiters to manipulate the Balkan Muslims through an arbitrary usage of their volatile identity, allocation of self-governing rights might come to cut stifling ambitions of religious leaders out of the Muslim minorities entirely by including them into the public sphere.

References:

[1] See More: Shenk G., “What Went Right: Two Best Case of Islam in Europe” p.20, in “Religion in Eastern Europe – Christian Associated for Relations with Eastern Europe”, Vol. XXVI n°4 – November 2006.

[2] See More: “The Balkans and The Middle East: Are They Mirroring Each Other?”, published by The Patriarchate of Peć and University of Belgrade, Faculty of Security Studies, October 14-15, 2012.

[3] Leview-Sawyer C. (2015) “Bulgaria: Politics and Protests in the 21th Century”, p. 110, Riva, Sofia.

[4] Cfr. Shenk G. (2006) Ibidem, p. 7.

[5] Cfr. Fukuyama F. (2011) “The Origin of Political Order”, Profile Books Ltd, p. 256.

[6] Cfr. M. Vickers M. (1998) “Between Serb and Albanian: A History of Kosovo”, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 19.

[7] See More “Albania and The Albanian Identities”, published by International Centre for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relation, 2000, Sofia.

[8] Cfr. Marinov M. (2017) “Religious Communities in Bulgaria”, South-West Bulgaria University Publishing House, Blagoevgrad, p. 70-74.

[9] See More: Mitja Velikonja, Religion in Eastern Europe, College Station Texas – University Press, 6/12/2003.

[10] In relation to Islam and interpretation of the sacred text of Quran, the transnational religious-political ideology of Salafism is an ultra-conservative reform branch or movement within Sunni tradition developed in Arabia in the first half of the 18th century.

[11] Stoilova Z., “The Roma and the Radicals: Bulgaria’s Alleged ISIS Support Base”, Balkan Insight, 11 January 2016 http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/the-roma-and-the-radicals-bulgaria-s-alleged-isis-support-base-01-10-2016-1#sthash.i0pOwSdR.dpuf, (accessed December 2016).

[12] See More: Ajzenhamer V., The Western Balkans and the Islamic Schisms. The case of Bosnia and Herzegovina, pp. 107-123, in Ibidem, October 14-15, 2012.

[13] Nawaz M. & Harris S. (2015) “Islam And The Future of Tolerance. A Dialogue” Harvard Publishing, pp. 17-20.

Francesco Trupia is a PhD Candidate trained in Political Philosophy at the Sofia University St Kliment Ohridski, where he also obtained his MA in Philosophy with a major in Intercultural Relations. Besides, he graduated at the University of Catania in Political Science and International Relations. After his sabbatical year in 2014, Francesco began to increase his interests in Eastern Europe by interning the NGO Focus in Bulgaria and the Refugee Project, working with vulnerable minorities. In 2016, he became one of the international fellows of the Yerevan-based Caucasus Resource Research Centre, exploring the links between minority issues and the conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh after the last constitutional reforms in the post-Soviet Armenia. While attending numerous summer schools in Russia, Serbia, Germany, Romania, Greece, Bulgaria, Armenia and Kosovo, in 2017 Trupia joined the London-based think tank Institute for Islamic Strategic Affairs – IISA by contributing for the Refugee & Border Control Program. He is currently a Field Officer in HOLDS Foundation, where he conducts mapping surveys in the post-Balkan Route scenario. Trupia’s current interests include minority groups and migratory phenomena over Eastern European contested territories. Counting on his fieldworks, he has presented his research in Turkey, Netherlands, Romania, Serbia and Bulgaria. His monograph on “Migranthood & Self-Governing Rights: A New Paradigm for Eastern Europe” has been recently published by Lambert Academic Publishing.

Hinterlasse einen Kommentar