Forward

Introduction

Chapter 1

1.1 Minorities and minority rights

1.1.2 The European Union

1.1.2 Actions by International Organisations

Chapter 2

- 2. Dealing with minorities as a state security issue in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe

2.1 The concept of security

2.2 The emergence of minorities in Central and Eastern Europe

2.3 The treatment of minorities over time

2.4 The factors that create state security problems

2.5. Theories and views on how to deal with the minority issue

2.6 Considering the minority issue through the prism of Anthropology

Chapter 3

- Case study of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria

3.1 The attitude of the Bulgarian state towards the Turkish minority in Bulgaria

minority and minority rights

3.1.1 The period 1878-1944

3.1.2 Communist era (1945-1989)

3.1.3 Post-communist period (1989 to date)

3.1.3.1 The institutional framework for the protection of minority rights

3.1.3.2 Political representation of the Turkish minority

3.1.3.3 Council of Europe findings on Bulgaria

3.2 Factors that make the Turkish minority a problem state security problem

3.2.1 The influence of the Muslim religion (Islam) on relations between the Turkish minority and the Bulgarian state and society

Conclusions

FOREWORD

Since its appearance on the Balkan scene, Bulgaria has shown a dynamic character and has clashed with all the great powers of each era. When the Turkish race arrived on the European continent, it further intensified the climate of the wider Eurasian region, which until the Balkan and World Wars remained acute. The relations between the two countries (Bulgaria and Turkey) passed through fire and iron, with successive exchanges of territory, cultural and social elements, resulting in a constantly volatile scene. Religion is historically considered an important institution for nations. In some cases it acts as a link in which the unity of each community is forged, while in other cases it is a deep dividing wall. In its cohesive capacity, religion has also functioned in the Balkan countries, where two of the world’s major religions, Christianity (Orthodox and Catholic) and Islam, meet. The emergence of nationalism as the political ideology of the Turkish leadership has helped shape bilateral relations with Bulgaria. The initial inward-looking approach to safeguarding what national interests were left over from the wars and the gradual economic stabilisation gave way to reconciliation and the formation of a new framework for cooperation between the two states. The dominant sector, both for the global economy and for individual states, is energy, with the result that Bulgaria and Turkey are converging in the same direction and turning to investments to serve their mutual interests. Bulgaria is now insisting on a European trajectory, while Turkey, on the other hand, is seeking to play a role in European developments in the Balkans. Bulgaria, like the other Balkan states, is trying to shake off what Turkey considers to be former Ottoman possessions. For these reasons, any ethnic issue raises reactions and touches on sensitive issues which can cause serious reactions.

INTRODUCTION

This paper deals with the issue of minorities, what rights their subjects have, as well as how Central and Eastern European states manage minorities, taking them into account as a matter of state security. More specifically, her problematic focuses on the specific case of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria and how Bulgarian society has dealt with it from the beginning of its creation as a newly established Bulgarian state from 1878 to the present day, while attempting to explain why it remains as a state security issue.

Regarding the content of the paper, initially the first chapter attempts a potential conceptual approach to the word minority, a concept that has not been successfully clarified entirely due to the wide range of opinions among European countries.

‚Then, in the second chapter, security is conceptualised, a historical review of the existence and formation of minorities in the aforementioned countries is given. At the same time, of very crucial importance, as described, is the situation that prevailed in Eastern and Central Europe after the collapse of the communist regimes due to the prevalence of social and political instability caused by the struggle of the world powers to spread their influence in these regions.

Subsequently, the case of the Turkish minority is examined and analysed with emphasis on the period after the fall of Communism in Central and Eastern Europe. This case is studied in relation to the institutional framework governing the environment of minority rights protection. It is worth noting that with reference to the institutional framework, the International Conventions and Declarations, the formed domestic legislation and political representation of Bulgaria are mentioned. Besides, the Turkish minority is connected with the religious factor and the relations developed in two countries, where in one country a large percentage of the minority is Muslim citizens and in the other country which is predominantly Muslim.

In summary, after a brief review of what has been written in the content of the paper, several as safe as possible conclusions will be carried out and an assessment of future developments will be made.

CHAPTER 1

- MINORITIES AND THEIR RIGHTS

The definition of the word “minorities” and people’s living conditions

Bulgaria is one of the relative newcomers to the European family, joining in 2007 after only 14 years of membership. Although living standards and socio-economic conditions do not converge with the European acquis, Bulgaria is trying to keep up with the European reality through reform projects. Given its European identity, the European influence on Bulgarian attitudes towards minorities deserves extensive mention.

Europe is considered to be one of the places on the planet where awareness of such social problems began very early in the consciousness of peoples. By way of example, the Council of Europe, one of the pillars of the European edifice, has been actively involved with minorities from the very beginning of its creation, i.e. in 1949.

Over time, its activity around minority issues became more and more intense and concerned, to a large extent, the protection of the subjects of minority groups. Thus, in 1994 the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities was considered one of the most important steps up to that time not only in protecting foreigners but also in asserting many of their rights. In essence, this Convention had a reinforcing and complementary role to what is provided for in the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.

With regard to the content of this Convention, this included many of the rights that foreigners have upon arrival and stay in their new country. For example, it talks about equality before the law, the use of their own language and the creation of their own communication networks, as well as education and, more generally, access to the economic, political, social and cultural life of their new country.

The European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms (1953), the European Social Charter (1965) and the European Charter for Regional and Minority Languages (1998) are also texts that provide for the protection of minorities.(16)

There have been several attempts to define minority rights in Central and Eastern Europe, but minorities themselves have rarely been involved in these discussions. The texts related to minorities usually reflected the views of states rather than minorities themselves. (17)

The Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe included minority rights in the 1990 Charter of Paris and the 1990 Copenhagen Document, and then went on to establish the High Commissioner on National Minorities (1993), who intervenes to resolve disputes concerning national minorities among its European member countries. (18)

It is an undeniable truth that the issue of minorities has been and still is one of the most important and critical issues in the world. Countries such as Greece or Bulgaria, which receive a particularly high number of immigrants and refugees every year, have many minority population variations in their population.

Although these minority groups are very small in number, they can cause various problems, particularly in the cities where they are concentrated. Before writing anything on the central theme of the paper, it would be useful to take a potential conceptual approach to the term „minority“.

Although it becomes very difficult to formulate a specific representative definition, it is generally agreed that it is considered to focus on a population group that is numerically smaller than the main group of local inhabitants of an area. The fact of the numerical superiority of indigenous people does not mean that foreigners did not enjoy social and human rights.

On the contrary, over time and through the long-term struggles of global organisations and NGOs, several rights have been won, for example, religion and language. Thus, people who come from other countries and reside temporarily or permanently in foreign territories retain their religious, linguistic and ethnic characteristics unchanged after their passage through the country.

In many cases, the common elements that unite these minorities help them to be more organised and have a sense of solidarity. Most foreigners share a common desire and aspiration to settle permanently and survive in their new places of residence.

Returning to the attempt to consolidate a conceptual definition, although the United Nations subcommittee came up with a definition, the majority of European countries, due to disagreements, did not converge on a common decision to clarify this concept.

The Council of Europe and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe focus more on Central and Eastern European countries than on Western countries in terms of minority rights policies. After all, the protection of minority rights in Western countries has never been the focus of international organisations. (19)

1.1.1. European Union

The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (7/12/2000 – Nice, France) in Article 21 (1) explicitly prohibits racial discrimination, discrimination on the grounds of colour, national or social origin, genetic features, language, religion or belief, political or any other opinion, and the inclusion of persons belonging to a national minority… “ (20)

According to the Copenhagen Criteria (1993), as supplemented at the Madrid European Council in 1995 (21) in order for countries to join the EU they must meet certain conditions, including respect for human rights and, by extension, for minorities. (22)

Already among the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, Hungary, Poland, the Baltic countries (Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia), the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia have joined the EU and have made great progress in the protection of minority rights.

1.1.2. Actions by International Organisations

As is commonly accepted by the world community and as reflected in world political history, the Soviet Union was one of the longest-lived multinational associations with a significant political impact on world developments, while at the same time being the most serious adversary of the United States during its 70-year history. Therefore, undoubtedly, its inevitable dissolution did indeed raise hopes for the Western World and its expansion, but it also caused many conflicts and upheavals both in Europe and in other parts of the world that were part of the Soviet blockade.

Both the United Nations and the European organisations were unable to prevent the conflicts that erupted in Europe after the collapse of the communist regimes and the dissolution of the multinational states of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia. But they did intervene to bring a cessation of hostilities, peace between the new states and the protection of minorities within them, as in Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, Kosovo, FYROM and Georgia. In the case of Kosovo (1998), NATO intervened militarily, without the prior approval of the UN, which was, however, subsequently granted.

Recent developments in Ukraine, with the secession of Crimea and its union with Russia, following the referendum of 16 March 2014 and the unrest in Eastern Ukraine, are being closely monitored by the UN. (23) The UN General Assembly adopted by a majority vote a non-binding resolution in support of Ukraine’s integrity, considers the Crimean referendum „has no validity and cannot be the basis for any change in the status of the peninsula“ and calls on „any country to refrain from acts affecting its territorial integrity“, implying Russia. (24)

The Council of Europe, with the Advisory Committee of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities as the competent body, assesses the implementation of the Framework Convention in Council member states and advises the Committee of Ministers (such as the decision of the Committee of Ministers (4/7/2012) referring to the WGM and pointing out discriminatory treatment of minorities). (25)

The Committee against Racism and Intolerance also deals with the situation of minority issues in Council of Europe countries, conducting inspections in European countries (see relevant 5th report of 16/9/2014 on Bulgaria). (26)

The Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe is trying to find solutions to ethnic disputes that may endanger peace and protects the rights of national minorities. (27) The OAS is also monitoring the latest developments in Ukraine, particularly in Crimea. In his report of 12 May 2014, the UN High Commissioner states of Ukraine „The situation of ethnic minorities in Crimea is very serious. Tatars are in a very dangerous position and Ukrainians have become an object of concern. “ (28)

The European Union with its competent institutions inspects the countries that have applied for membership to see if they meet the Copenhagen Criteria on the protection of the rights of national minorities and only in a positive case, if the other Criteria are also met, approves the country’s application for membership of the Union. Already most Central and Eastern European countries have become members of the EU, while the candidate countries for membership are Serbia, Montenegro and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and potential candidates are Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo.

Chapter 2

- The treatment of minorities as a state security issue in Central and Eastern European countries

2.1 The concept of security

„Security is taken to be about the pursuit of freedom from threat and the ability of states and societies to maintain their independent identity and their functional integrity against forces of change, which they see as hostile. The bottom line of security is survival, but it also reasonably includes a substantial range of concerns about the conditions of existence. Quite where this range of concerns ceases to merit the urgency of the „security“ label (which identifies threats as significant enough to warrant emergency action and exceptional measures including the use of force) and becomes part of everyday uncertainties of life is one of the difficulties of the concept“ -Barry Buzan, „New Patterns of Global Security in the Twenty-first Century“, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Vol. 67 No.3 (1991), pp. 432-433.

The concept of „security“, according to John Baylis, is „controversial“ among authors, who converge „on protection against threats to core values (individuals and groups)“ and disagree on the priority of ’national‘, ‚international‘ or ‚individual‘ security. (29)

One of the key theorists of the Copenhagen School (30), Barry Buzan in a broad analysis of security issues, which he sees as arising after the end of the Cold War and in the run-up to the 21st century from the formation of new relations and balances between major powers and regional states, defines ’security‘ as ‚the pursuit of freedom from threat and the ability of states and societies to maintain their own independent identity and functional integrity against forces of change which they see as hostile, and the essence of security is survival‘. (31)

Buzan goes on to distinguish security into five domains, military32, political33, economic, social34 and environmental, which are not independent but interrelated. (35)

According to Ole Waever, the second of the key theorists of the Copenhagen School, „During the 1980s there was a general movement to broaden the concept of ’security‘ and one approach was to move from a strict focus on the security of the state (national security) to a broader alternative focus, on the security of people either as individuals or as a global or international collective. National security, i.e. the security of the state, is the concept of an ongoing debate, but an abstract idea of security is a non-analytical concept that has little to do with the notion of security implied by national or state security. “ (36)

Copenhagen School theorists argue that an international security problem can be understood in terms of military-political security and that the concept of security is identical to survival when an issue poses an existential threat that legitimizes the use of state power and allows for the imposition of emergency measures to deal with it. (37)

2.2 The emergence of minorities in Central and Eastern Europe

The existence of minorities is a global phenomenon, found in every country on earth. In Europe in recent centuries there have been large-scale population movements due to economic and political unrest and wars and created multi-ethnic states and minorities within them. (38)

With the influence of the French Revolution of 1789, the issue of minority protection became very important in Europe in the 19th century and the concept of human rights was linked to the concept of nationality. The emergence of nationalism brought new minority issues to the fore. In Central and Eastern Europe, many ethnic groups retained their identity (language, culture) and in the process began to claim more rights, such as the use and education in their native language. (39) According to Vladimir Ortakovski, „in Central and Eastern Europe, nationalism demanded that each nationality form its own state and that each state consist of only one nationality, which was recognizable by its language. “ (40)

In the 19th century, Central and Eastern Europe was included in the multiethnic empires of Austro-Hungarian, Ottoman, Germanic and Russian. (41) These empires were dissolved as a consequence of the First World War and new states were formed. (42) As Ortakovski points out, „minorities were a cause of tension between their states of origin and the states in which they lived after the redrawing of borders“. (43)

Border changes after wars, the prevalence of communism in Russia in 1917 and in Central and Eastern Europe after the end of World War II, and more recently the collapse of communist regimes and the dissolution of the multi-ethnic states of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, resulted in all the new states in which groups of people belonging to a different ethnicity from the majority of the population remained and constituted minorities. After the conflicts that took place in the territories of the former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union, the main minorities in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe today are the following: the German minority in Poland, the Slovak minority in the Czech Republic, the Hungarian minority in Slovakia, the Roma in Hungary, the Czech Republic, Romania and Bulgaria, the Russian minority in Ukraine, the Tatars, Ukrainians and Chechens in the Russian Federation, the Serbian minority in Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Kosovo, Hungarian in Serbia (Vojvodina), the Albanian minority in the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, Greek in Albania, Hungarian in Romania and Turkish in Bulgaria.

Accurate statistics on minorities do not exist in European countries, as many states for national reasons do not recognise as minorities all population groups with different languages, religions, traditions and historical backgrounds. (44)

2.3 The treatment of minorities over time

Minorities have always been treated with mistrust and often with prejudice by the ethnic majority and the states in which they lived, often resulting in persecution and violent treatment.

After the end of World War I, minorities trapped within the new nation states were eventually marginalized. (45) After World War I and before World War II, the states of Central and Eastern Europe often violated the rights of minorities imposed by the League of Nations. During World War II, minorities suffered large reductions in their populations due to ethnic cleansing and genocide (Jews), mass movements and changes in the territorial territory of states. (46)

During World War II, when the Axis powers had conquered a significant part of Europe, they proceeded to annex territories. After the defeat of the Axis, these territories were returned to the states to which they belonged. (47) During the War, minorities found themselves in a difficult position and suffered persecution, which deeply affected the relations between peoples (nations) in the long run since then and until today. (48)

During the communist period in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, many ethnic groups lived together in multi-ethnic states, such as in the Soviet Union, Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia. The communist regimes left no room for nationalist conflicts and the emergence of minority nationalism.

The end of the Cold War brought border issues back to the forefront, and the reunification of East and West Germany brought down the most important border of the Cold War era, marking a nationalist revival, while in Eastern Europe strong tendencies for border redrawing are emerging. (49) The situation of minorities worsened after the collapse of communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe and the resurgence of nationalist conflicts. (50) The phenomenon of nationalism re-emerged in Europe after the end of the Cold War and the major changes that occurred in Central and Eastern Europe, such as the break-up of Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia. Nationalism leads to xenophobia, threatens the protection of minority rights as well as peaceful relations between states. (51) The history of the last period, from the collapse of communism to the present day, has shown us with many examples that democracy and nationalism are incompatible paths. (52)

As Barry Posen argues, the collapse of the multi-ethnic communist regimes of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia brought to the surface the state of anarchy throughout their former territories. After the absence of the domination of the state, the various groups, both ethnic and religious, were faced with the problem of their security. (53)

According to realist theory, the feeling of insecurity felt by states is due to the state of anarchy. (54) The situation would be different if states did not act independently and competitively in order to survive and show power. (55) Competition will lead to the concentration of power greater than necessary for the security of the competitors, and as a result they pose a threat to their neighbours, who, feeling insecure, react and strengthen their power. These states and their rulers do not realize that these actions are perceived as threatening by others. (56) According to Barry Posen, the „security dilemma“ is: „the actions one takes to enhance one’s own security provoke reactions that may ultimately make one less secure. “ (57)

According to Harry Mylonas, „the ’nation-building‘ policies pursued by the dominant elites of host states towards minorities are three: housing, assimilation and exclusion“. 58 Mylonas goes on to explain that with the policy of ‚housing‘ the ruling elites keep minorities in the state, to which they grant certain minority rights on the basis of laws and related institutions; with the policy of ‚assimilation’59 they apply various tactics (educational, cultural, vocational, etc.) with the aim of integrating the minority into the lifestyle of the majority; and with the policy of „In the context of the ‚exclusion‘ policy, they attempt the physical removal of the minority, through population exchange, deportation or even mass extermination (as in the case of Bosnia). (60)

Minorities and majorities, because of their diversity, are often at odds over many issues. (61) It is very difficult for states today to provide fair and definitive solutions to these issues, and the emergence of nationalist conflicts in Eastern Europe prevented the establishment of democratic institutions. In the historical past, states have pursued various policies with regard to minorities with the aim of achieving homogeneity, implementing mass deportations, assimilation policies and in other cases isolating minorities and denying them political and economic rights. (62)

After World War II, the view prevailed that there was no need for a specific reference to the rights of ethnic minorities, as they are included in human rights, which is why the United Nations in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights does not mention minority rights. (63)

It subsequently became apparent that this affiliation could not solve the problems of minorities, such as the use of the minority language in public life, education in the mother tongue, the drawing of internal borders and participation and in what proportion in political representation. These issues, according to Kymlicka, have been left to the jurisdiction of the majority, resulting in unfair treatment of minorities and this subsequently exacerbates relations between them, and therefore their just resolution requires the coupling of human rights with minority rights. (64) This has been dramatically demonstrated in the countries of Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, where the above issues have led to violent conflict and there is no prospect of lasting peaceful coexistence until they are resolved. Consequently, minority rights have rightly come to the forefront of international relations and have been included in the Declarations of international organizations, but without clearly defining their scope. (65)

In the new states that emerged after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia, ethnic minorities remained cut off from their fellow nationals, who sought to secede, with the help of the state in which their ethnicity constituted the majority of the population. The rise of nationalism led to wars in the countries of the former Yugoslavia between Croats and Serbs in the region of Krajina, where there is a Serb minority, and between Bosnian Muslims, Croats and Serbs in Bosnia-Herzegovina,

between Serbs and Albanian Kosovars in Kosovo, as well as in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia between Slavo-Macedonians and Albanians, and even ethnic cleansing and genocide in Bosnia-Herzegovina (Srebrenica, 1995) by Serbs against Bosnian Muslims, events that had not occurred in Europe since World War II, when Hitler’s Nazi Germany had mass exterminated Jews and Roma in concentration camps. In Kosovo, NATO intervened militarily against the Serbs in 1999 to protect the Albanian minority and forced the withdrawal of the Serbian army, then the UN took control of the region and in 2008 Kosovo declared independence.

In the countries of the former Soviet Union, wars broke out in Georgia (Abkhazia and Ossetia), Azerbaijan (Nagorno-Karabakh), Moldova (Transnistria) and Russia (Chechnya). (66) More recently, in 2014, following a referendum on 16 March 2014, Crimea decided to become independent from Ukraine and proceeded to join Russia, while in Eastern Ukraine the Russian minority also took armed action with the same aim, without ultimately succeeding, following the intervention of the international community.

It is noteworthy that in the countries of Central Europe after the collapse of the communist regimes, no military conflicts took place, despite the existence of national minorities in each country, while the separation of the Czech Republic and Slovakia took place peacefully and no nationalist conflicts followed, although a Slovak minority remained in the Czech Republic.

According to George Schopflin ‚the problems of national identity, nationalism and ethnic minorities in post-communist Central and Eastern Europe emerged with an unpredictable and unexpected toxicity‘. (67) The communist era had a significant impact on these countries. After World War II, Western countries dealt with nationalist pressures within the framework of democratic institutions, which was not possible in the communist era.

Schopflin goes on to point out that the essential difference between the two sides is the different approach to the question of citizenship. In Central and Eastern Europe the new democracies are trying to find their way and create the institutional frameworks within which citizenship will be included. (68)

In the Central and Eastern European states, according to Barbara Tornquist Plewa, there is a differentiated minority policy in each country: Hungary conducts a policy that is friendly to minorities; Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovenia maintain a neutral position; Lithuania is trying to find a modus vivendi; (69) while Estonia and Latvia are clearly pursuing an assimilationist policy. (70) The Hungarian minority in Romania and Slovakia and the Polish minority in Ukraine, Belarus and Lithuania enjoy support from Hungary and Poland respectively, having a political weight within the states where they live. Although minorities in Eastern European countries (such as Bulgaria and Lithuania, which make up a quarter of the population, and Poland and the Czech Republic, which do not exceed 10% of the population) are not significant in number, they are nevertheless of particular importance in Central and Eastern European countries, and this is due to the attitude of the majority towards minorities, as they see them as a potential threat to their identity, an issue which is of great importance to the majority and is rooted in the historical past.

The concepts of ’state‘ and ’nation‘ are two distinct concepts in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. This is due to the fact that the new states appeared later than the nations. In these countries, nationalism, unlike in Western countries, where it contributed to the strengthening of the state and the homogenisation of the population, moved in a divisive and segregating direction. The new nations were not created within existing states, but by the division of these states into smaller ones, based on different ethnic and cultural identities. (72)

The CEE countries, which are members of the EU, grant minorities the minority rights provided for in the UN Declaration and the Framework Convention of the Council of Europe, detailed above, while the other countries are also lagging behind in this area.

2.4 The factors that create state security problems

I believe that the critical issue, which creates state security problems, is the claim of territorial autonomy by ethnic minorities, which all states see as a real threat to their territorial integrity. States that have on their territory ethnic minorities with a significant number of persons living in areas bordering their state of origin face a serious security problem and fear that the minorities have the ultimate goal of autonomy and unification with their compatriots, as has happened in the past in many cases (the Hungarian minority in Romania).

Minority rights, as provided for in international conventions and declarations, do not include the right to grant territorial autonomy to minorities.

The issue of autonomy negatively affects majority-minority relations and is defined on three levels, personal, cultural and territorial. (73) Territorial autonomy is the most critical level, the one that creates a crisis in majority-minority relations. In the countries of post-communist Central and Eastern Europe, majorities consider that the claim of territorial autonomy by minorities conceals aspirations for secession and threatens the integrity of the state, constituting a „red rag“ for minorities. The dissolution of Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union and the creation of the new states on the basis of internal borders set by the communist countries, shaped the negative attitude of the majorities towards further territorial changes. (74)

Territorial autonomy to ethnic minorities has been rejected by all countries except Russia, which has granted it to several minorities. (75) While during the communist period many states had granted territorial autonomy to ethnic minorities, immediately after the fall of the communist regimes the newly independent states were quick to revoke it. (76) In other cases, requests for the restoration of territorial autonomy, which they had previously enjoyed, were rejected (such as the Hungarian minority in Romania), while in other cases requests for territorial autonomy, raised for the first time, were not accepted. (77) Some countries modified the internal division of the state’s regions in order to weaken the areas inhabited by ethnic minorities and to exclude the possibility of recognising autonomy for these areas in the future. (78)

In the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, the autonomy of minority regions was in most cases violently asserted and led to a civil war, the outcome of which determined the fate of the minority. Cases where de facto territorial autonomy was recognised after military conflicts are the case of Transnistria in Moldova (Russian-speaking), Abkhazia in Georgia (Russian-speaking) and Nagorno-Karabakh in Azerbaijan (Armenians). (79) In contrast, in the case of Krajina in Croatia, where Croats ultimately prevailed over Serbs, the autonomy of the region was revoked. (80)

Developments in Kosovo and the recent events in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine in 2014 and the move by Transnistria (81) to seek union with Russia significantly affect the minority policy of the Central and Eastern Europe and cause concern that other ethnic minorities may attempt similar moves in the regions where they constitute the majority of the population, in order to achieve independence and secession from the country to which they belong, creating a feeling of insecurity in these countries.

As Charis Mylonas points out, three subjects are at work in the minority issue, a host state, a minority and an external power (state) bordering the first, and state-minority relations depend on the relations between the state and the external power and on the influence of the external power on the minority. (82)

Schopflin argues that „the subjugation of Central and Eastern Europe to communism was seen by the nations of the region as a new foreign suzerainty, and opposition to communist rule progressively led to the strengthening of national identity. The consequence of communism was that these states found themselves in the transition to the post-communist era unprepared for democracy. “ (83) Communism, according to Schopflin, unexpectedly led to the development of „ethnic nationalism “ (84) to which some communist regimes, such as Ceausescu’s in Romania, contributed. (85)

The case of Slovakia is a typical example of ethnic nationalism, which led to the break-up of Czechoslovakia, despite the great linguistic affinity between the two peoples, as Slovaks were perceived to be oppressed and in a subordinate position to Czechs within the Czechoslovak state. (86) The feeling that they had been humiliated by the Hungarians in the past, when they were part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, determined the attitude of the Slovaks towards the Hungarian minority, which continued to reside in the south of the country. Despite the fact that a fifth of the population was made up of non-Slovaks, Slovak nationalists wanted an ethnically pure Slovakia and this intensified their antipathy towards the Hungarian minority.

As a result of its policy against the Hungarian minority, Slovakia accepted the remarks of the Council of Europe. (87)

According to Schopflin, a distinction should be made between two categories of minorities, those that have been established in the region where they have been living for a long time and those created after recent migrations, which face difficulties in integrating into the whole but the majority do not see them as a threat to the security of the state. In contrast, minorities living in a certain territorial area for a long time are seen by the majority as a threat to state security. (88)

Post-communist thinking and mentality, according to Schopflin, sees ethnicity as the only guarantee for the solution of all problems at all levels, views the world with suspicion and fears the diversity of other individuals, influenced by communist thinking and mentality. (89)

There is also a tendency, after the communist period, during which social structures were destroyed, to treat all issues, even economic issues, to which the rules of economics should be applied, with ethnic criteria, and a tendency to blame foreigners for their unfavourable economic situation. (90)

The different religion of the minority is an important factor, which complicates the relations between the minority and the majority (such as the Serbian minority (Christian Orthodox) in Croatia (Catholics) and in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Muslims) and especially the Muslim religion after the last terrorist acts. Also the economic problems faced by the above countries since the collapse of Communism are a factor that does not favour minorities, as the majorities are also in a difficult situation.

2.5 Theories and views on how to deal with the minority issue

In democracies, which lack strong foundations, the state tends towards nationalisation and serves the interests of the ethnic majority. It is obvious that the minority should operate within the framework defined by the majority unless the two sides come to an agreement to settle the issue of autonomy. (91) Nationalisation of the state brings about mutual fear and suspicion and tension in the relations between the two sides, as minorities lose acquired rights (92) and consider themselves marginalised, as the state only serves the interests of the majority, and as a result they no longer trust the state. (93)

According to Will Kymlicka, ‚minority nationalism is a global phenomenon and ethnic minorities come into conflict with the state to which they belong, either peacefully or violently, to achieve political representation, language rights, political autonomy, control over wealth resources and internal movement‘. (94) The way minority nationalism is dealt with by the states of post-communist Central and Eastern Europe is very different from that of Western countries. In particular, Western countries, accepting the principle of justice, consider minority nationalism and the granting of territorial autonomy to minorities as legitimate, in contrast to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, which promote the principle of state security, considering territorial autonomy as a threat to the security of the state. (95)

Kymlicka asks whether the way Western countries have dealt with their own cases of minority nationalism can be applied to the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, and whether the transition to full-fledged democracy and economic prosperity in these countries will resolve minority problems. In his opinion, these conditions are not sufficient for the CEE countries, because the problems of minorities are more difficult in these countries. The Western organizations set as a condition for the membership of CEE countries the protection of minority rights, aiming at the same time, on the one hand, to ensure security in these states and, on the other hand, to achieve fair treatment of minorities by the states. Kymlicka is opposed to this approach to the issue by the West and argues that justice and security are two incompatible paths for CEE countries, in which the issue of minority rights is „secured “ (96) and that fair treatment of minorities can only be achieved in „de-securitization“ of the issue. (97)

One of the first actions of the CEE states was to pass laws to safeguard the language and culture of the majority and the security of the state, rather than to pass laws to democratize and reform the economic reforms of the transition to a market economy. Such an example is the constitution of post-communist Romania, which leaves no room for minority autonomy claims, stressing that Romania is „a single and indivisible state“. A similar provision is contained in the 1991 Constitution of Bulgaria, which leaves no room for claims of territorial autonomy. However, when states marginalise minorities by not recognising their rights, it follows that minorities will feel resentment and treat the state with distrust and hostility, resulting in tension between minorities and the state and the state worrying about its security. (98)

The securitisation of minority issues leaves no room for moral arguments and democratic dialogue. While in Western countries minority claims, when made in a peaceful manner and democratic processes, are tolerated and only in the case of the diversion of minority nationalism into terrorist acts, the issue is secured (Basque case in Spain), in CEE countries the claims for territorial autonomy, education in the minority language at a higher level, collective rights and official language are perceived as a threat to state security and only demands that are considered harmless, such as basic education in the minority language, are tolerated. (99)

Kymlicka argues that the securitization of minority nationalism in CEE countries can become harmful not only to minorities, but to democracy and peaceful coexistence within the state. Countries such as Hungary, Poland and Slovenia, which did not have a strong element of minority nationalism, have been able to democratise successfully, while countries such as Serbia, the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and Ukraine, with a strong element of minority nationalism, have had difficulty. Most Central and Eastern European states, while projecting a liberal democratic face, have refrained from granting minorities all their democratic rights. (100)

To the question of what the international community can do to help the „de-securitization“ of minority issues in CEE countries, according to Kymlicka, one option is, after taking into account the fear, prevalent in CEE countries of territorial secession, that the issues of territorial autonomy and secession should be separated. To this end, the international community must convince the CEE states that granting territorial autonomy to minorities will not result in the secession of territories from the state, while giving states strong guarantees of their unity and territorial integrity and obliging minorities to pledge their loyalty to the state and the immutability of its borders. In addition, the international community should persuade minority-affected neighbouring states to cease all territorial claims by signing agreements to this effect. (101)

The international community has already applied this option to the CEE countries with little success, however, as these countries do not trust the guarantees regarding the inviolability of the borders, because the attitude of the international community, especially the Western states, is not credible, as they face different same cases, depending on their interests. Thus, for example, while in the cases of Abkhazia and Transnistria they did not accept de facto secessionist situations, in the cases of the former Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia they immediately recognized them. (102) The most important objection, however, according to Kymlicka, is that the international community, even if it guarantees the territorial integrity of a state that grants territorial autonomy to the minority, will in practice be unable to prevent secessionist movements by the minority and possible civil war. (103)

According to James Mayall, the conditions are not ripe for the international community to change its position on the issue of self-determination and territorial autonomy of minorities by consenting to grant them these rights and by derogating from the principle of state sovereignty, as many countries, such as China and Third World countries, are opposed to these changes, especially after the failure of both Europe and the international community as a whole to prevent the dramatic events in Bosnia-Herzegovina and the countries of the former Soviet Union. (104) Asking what are the necessary conditions for the protection of national minorities in a new transnational regime, he states that „it is first necessary to separate cases from needs, as neither states nor minorities are in the same situation“. (105)

I consider that, at this stage, CEE countries cannot grant minorities more rights than those already granted and provided for in the International Conventions-Declarations, especially territorial autonomy, which is not provided for as a right. The events that took place after the collapse of the communist regimes in the CEE and especially in the countries of the former Yugoslavia and the former Soviet Union after their dissolution have decisively influenced the attitude of the majority in all countries towards minorities and strengthened the fears for the security of the state.

With the completion of the transition of the post-communist CEE states to full democratic functioning and the achievement of economic development, differences between ethnic and religious communities will gradually become less pronounced and when every fear and suspicion of the majority towards minorities and vice versa of the minority towards the majority is eliminated, the idea of federalization of the regions of the state, with the granting of territorial autonomy to minorities, can mature and be accepted by the majority. After all, neither the EU recognises territorial autonomy as a minority right nor does it want border changes. On the other hand, the accession of many of the above-mentioned countries and the intended accession of the others to the European Union works to the benefit of minorities, since the EU requires countries to respect minority rights, which it includes in the Copenhagen Criteria for accession.

Ethnic nationalism, which is still prevalent in all the states of post-communist Central and Eastern Europe, creates obstacles to the development of good inter-ethnic relations, both within each country (majority-minority) and in relations between states. The accession of these countries to the European Union will gradually mitigate ethnic differences and improve relations between nationalities and states, reducing the influence of ethnic identity and shaping a common European identity, which is what the proponents of European integration are looking forward to.

Willfried Spohn states that ‚European identity is seen primarily as a derivative of the emerging transnational constituent framework of the European Union‘. (106) European identity is divided into two levels, European cultural identity (first level) and European integrated identity (higher level). (107) The post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe, those that have joined and those that aspire to become members of the European Union, claim to possess a European cultural identity and that by participating European identity means that national identities will simultaneously recede, as well as the nation-state, which will be gradually replaced by European institutions in the context of European integration.(108) Continuing his analysis, Willfried Spohn points out that the accession of the Eastern Europe’s integration into the European Union is seen by both sides (Western and Eastern countries) ‚as a guarantee for the prevalence of peace and security, the stabilisation of post-communist democracies, and the achievement of economic growth and prosperity‘. (109) Willfried Spohn argues that the formation of an integrated European identity will require a long and difficult process in the course of European (Eastern and Western) integration. (110)

Chapter 3

- Case study of the Turkish minority in Bulgaria

3.1 The attitude of the Bulgarian state towards the Turkish minority and minority rights

3.1.1.1.

The conquest of Bulgaria by the Ottoman Turks at the end of the 14th century, in the 1390s, resulted in the settlement of an Ottoman population on its territories. (130) After the liberation of Bulgaria and the creation of an autonomous Bulgarian state by the Treaties of St. Stephen and Berlin in 1878 (131), a part of the Turkish population remained in the country. In the 1880-1881 census the total population of Bulgaria was 2,823,865 people, of which 1,919,067 were Bulgarians (67.96%) and 701,984 people of Turkish origin (24.86%). (132) Since then there has been a gradual decrease in the Turkish population, due to migration to Turkey, and in 1910 the percentage of the Turkish population was 11.63% of the total population. (133) A massive exodus of the Turkish population took place in 1913-1914 after the Balkan wars. (134)

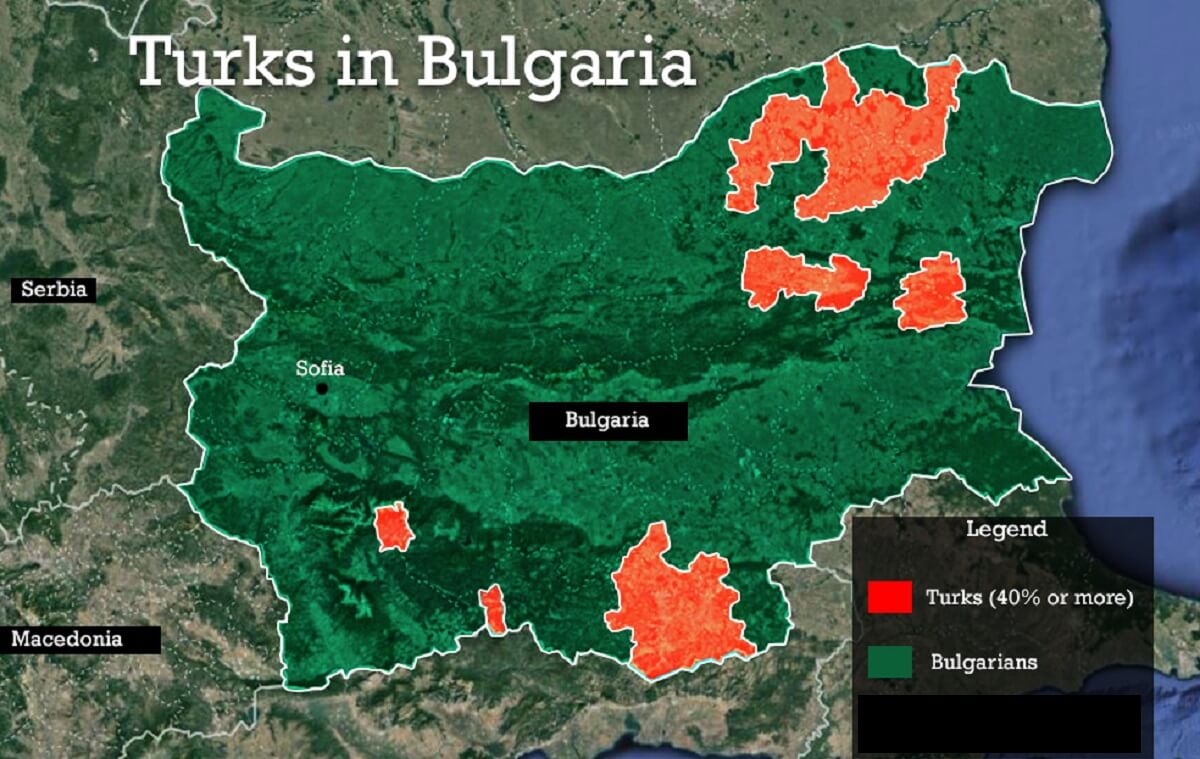

The Turkish minority is mainly concentrated in the southern regions of the country, in the Arda River basin and in the northeast in the Dobruja region. They also live in scattered communities in the regions of the Aemos Mountains (Stara Planina) and Rhodope. (135)

The 1878 Treaties of St. Stephen’s and Berlin included Bulgaria’s obligation to protect minorities, while the Turnovo Constitution (1879) in Article 57 provided for equality before the law for all Bulgarian citizens. Then after World War I, Article 50 of the Treaty of Neuilly obliged Bulgaria to sign a treaty for the protection of minorities and „to ensure full protection of the life and freedom of all inhabitants of Bulgaria, without distinction of birth, nationality, language, race or religion“. (136)

But political action, according to Ali Eminov, was directed from the outset towards the formation of „a nation-state territorially, culturally and linguistically unified, eliminating cultural diversity through assimilation or immigration of the country’s ethnic minorities“, taking as a given that: nation = language = territory = territory = state. (137)

3.1.2 Communist era (1945-1989)

Bulgaria and Turkey, after the end of World War II, signed various agreements allowing the movement of minority members to Turkey and it is estimated that by 1978 about 200,000-280,000 people had emigrated. According to the 1965 census, it is estimated that the Turkish minority numbered 746,755 persons.

The first Constitution of Communist Bulgaria in 1947 granted rights to minority groups, such as in Article 71 which provided that „ethnic minorities have the right to be taught the spoken language and to develop it, as well as to develop their national culture“. Thus, with regard to the Turkish minority, a department of Turkish Studies was created at the University of Sofia, publications were made in the press in Turkish and emphasis was placed on the development of their culture and, by extension, their mother tongue. (139) The establishment of schools for the Turkish minority was particularly encouraged. (140)

Subsequently, however, we observe a radical shift in Bulgarian policy towards the Turkish minority, brought about by the change of attitude of the Bulgarian Communist Party, which led to the merger of the minority schools with the Bulgarian schools, later to the abolition of Turkish language teaching in Bulgarian schools, and in 1974 to the cessation of the Department of Turkish Studies at Sofia University. Other measures taken against the Turkish minority included a ban on the participation of members of the minority as officers in the police and the army, while those who were conscripted to serve their military service in the army were employed in unarmed units, an attitude which, according to Hugh Poulton, showed the lack of confidence Bulgarians had in the Turkish minority. (141)

The 1971 programme of the Bulgarian Communist Party stated as its aim to bring citizens of different nationalities closer together, and the phrase

„unified Bulgarian socialist nation“ dominated public discourse. While the 1947 Constitution recognised ethnic minorities, the 1971 Constitution referred to ‚citizens of non-Bulgarian origin‘ (Article 45). From 1985 to 1990 Bulgarians recognized as minorities only Jews and Armenians, who did not number many people. (142)

In the late 1970s, Bulgarian policy put pressure on the Turkish minority to change Muslim names to Bulgarian and abandon the Muslim religion. The Bulgarian authorities viewed the Islamic religion with distrust and saw it as a factor that distanced the minority from coming closer to communist ideology and practice. The Bulgarian press showed its distrust and dissatisfaction with the Muslim religion in every possible way, publishing in various newspapers, such as Nova Svetlina (1985): ‚fasting in the month of Ramadan was nothing but a destructive superstition‘. (143)

In the period from 1984 to 1989, the last of the communist period, Bulgaria implemented an assimilationist policy towards the Turkish minority. The Turkish minority was forced to change their names and many members were accused of espionage because of their opposition to this policy. Other measures included a ban on traditional Turkish clothing and the Turkish language in public places. (144) The Turkish minority reacted to this policy with mass protests in early 1989, but the Bulgarian state proceeded with repressive actions and expulsions, resulting in 300,000 members of the Turkish minority having left Bulgaria for Turkey by August 1989. (145)

3.1.3 Post-communist period (1989 to date)

According to the 1992 census, out of a total population of 8,487,317, the Bulgarians were 7,271,185 (85.67%) and the Turkish minority 800,052 (9.43%), while in the 2011 census the total population was 7,364,570, the Bulgarians 5,664,624 (84.8%) and the Turkish minority 588,318 (8.8%) persons (second largest ethnic group). (146)

On 10 November 1989 Todor Zhivkov, the head of the Bulgarian state, was deposed and Petar Mladenov was appointed as the new head of state. Soon Bulgaria’s minority policy changed and the laws on which the previous repressive policy had been based were abolished. Thus members of the Turkish minority who had been exiled were returned to their place of residence and those who had been convicted for actions against the state were released. On 29 December 1989, a government decision was taken, by which the Turks in Bulgaria were allowed to have their Turkish names again, perform their religious duties and use their mother tongue in their lives. (147)

3.1.3.1 Institutional framework for the protection of minority rights

The 1991 (148) Constitution provides for: „the Republic of Bulgaria shall be a unitary state“, „no territorial autonomy shall be allowed within it“ and „territorial integrity shall be inviolable“ (Article 2). Article 3 states: „Bulgarian shall be the official language of the Republic“, Article 6 (para. 2) provides: „all citizens shall be equal before the law and any privilege or restriction of rights on the basis of race, national or social origin, ethnic self-identification, gender, religion, education, opinion, political belief, personal or social status or property shall be prohibited“, while article 11 (para. 4) does not allow „political parties with ethnic, racial or religious characteristics“. (149) Here we should note that Bulgaria is the only European country whose Constitution prohibits the establishment of political parties with religious or ethnic content. (150)

Article 13 provides that „the practice of worship of any religion shall be without restriction“ (para. 1); „religious institutions shall be separate from the state“ (para. 2); „the Eastern Orthodox Christian religion shall be considered the traditional religion in Bulgaria“ (para. 3); „religious institutions and communities and religious faith shall not be used for political purposes“ (para. 4). (151)

Article 29 (para. 1) stipulates that no person shall be subject to „forcible assimilation“. (152)

The Constitution gave a wide range of rights to citizens of non-Bulgarian origin and removed the legislative ban on the teaching of the Turkish language. The Constitution provides: „citizens, for whom the Bulgarian language is not their mother tongue, they are entitled, at the same time as the compulsory study of Bulgarian, to study and use their mother tongue“ (Article 36, para. 2). (153)

Article 37 provides that „freedom of conscience, freedom of thought and choice of religion and religious or atheistic views shall be inviolable“ (para. 1) and „freedom of conscience and religion shall not be exercised to the detriment of national security, public order, public health and public values or to the detriment of the rights and freedoms of others“ (para. 2). (154)

According to the Constitution, „Everyone has the right to use national and cultural values and to develop his culture in accordance with his national origin, which is accepted and guaranteed by law“ (Article 54(1)). (155)

As Maeva M. points out, in application of the above provisions of the Constitution, in November 1991, the Government issued a decree permitting the study of the mother tongue as an optional subject in school education and Turkish language began to be used in the media. (156)

Bulgaria became a member of the Council of Europe in May 1992 and in December 1992 signed a cooperation agreement with the EU, which included protection of the rights of national minorities. (157). On 21 September 1998 Bulgaria signed the European Social Charter and ratified it on 7 June 2000 (158). The Bulgarian government signed the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities in October 1997 and ratified it in 1999. (159)

In its Action Programme 2000, the European Commission expresses its opinion on Bulgaria’s application for membership of the European Union: ‚Bulgaria continues to respect human rights and freedoms, has ratified the Council of Europe’s Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities, has made good progress in bringing its legislation into line with European standards, and recognises that some steps need to be taken to address the problems of minorities‘. On the Turkish minority, he notes: „it is adequately represented in political life at both national and local levels, in contrast to its low representation as officers in the army and public administration. Education, both primary and secondary, of the minority should also be improved. In the end, the Commission concludes that Bulgaria fulfils the Copenhagen Criteria for accession to the European Union. (160)

The European institutions have played an important role in establishing legal guarantees for the protection of national minorities in the Balkan countries. Important steps towards the formal recognition of the Turkish national minority were taken by Bulgaria with the signing of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities in 1997 and the meeting of Turkish ministers with the Bulgarian government in 2001. (161)

The National Assembly passed the new Law on Religions in December 2002, which guarantees equal treatment regardless of one’s religion. The European Commission in its annual reports (1998-2004) notes Bulgaria’s progress towards accession to the European Union in terms of human rights and that it fulfils the criteria set by the European Council in Copenhagen in 1993. (162)

Maeva M. concludes that over the last 15 years (1989-2004) Bulgaria has achieved much to improve the situation of the Turkish minority and has made strenuous efforts to bring its legislation into line with European legal standards, to create sustainable democratic institutions and to improve the situation of the Turkish minority.

An important step, according to Maeva, is the enactment of the Protection from Discrimination Law (2003) and the continued efforts of the National Council for Ethnic and Demographic Issues to solve the problems of the Turkish minority in the country (since 1997). (163)

Bulgaria has included in the Criminal Code crimes of racial, national or ethnic hatred or motivated by religion (hate speech, violence, mob violence, intimidation) (articles 162, 163, 164, 165) and has imposed increased penalties for homicide and bodily harm (articles 116, 131). (164)

On 14 June 2004, the European Union accepted that Bulgaria met all the conditions for membership and decided that it would become a member of the European Union as of 1/1/2007, which it did. (165)

By joining the European Institutions, Bulgaria formally recognises a Turkish/Muslim minority, both national and religious, and guarantees the exercise of the rights protected by all the above-mentioned relevant Conventions. To this end, the assistance of the European Union is also important. Bulgaria is no longer an isolated country and the Turkish/Muslim minority has the right to look forward to a better future. On the other hand, the political benefit for Bulgaria itself is the reduction of the internal tension caused by the minority issue and the achievement of stability, which has the effect of preventing internal state security risks. In addition, its membership of the European Union ensures its territorial integrity.

The Turkish minority, as Maeva points out, wanted Bulgaria to join the European Union, as it believed that after accession there would be economic growth and thus a better quality of life in the country. Members of the minority also believed that within the European Union they would be European citizens, enjoy the benefits of European culture and have their rights protected. (166)

3.1.3.2 Political representation of the Turkish minority

On 4 January 1990, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) was founded by Ahmed Dogan. Its primary objective was to defend the ethnic and religious freedoms of the Turkish minority, as it claimed and that it was not a political party, as the establishment of parties with ethnic and religious characteristics was prohibited, and soon in February 1990 it had 100,000 members. (167)

In the elections of 10 and 17 June 1990, the C.D.E. won 23 seats in the Grand National Assembly. On 28 June 1990 the government, after several protests against the Movement, declared that organisations and movements that were not political parties could participate in the elections under the new electoral law. The KDP, under the leadership of Ahmed Dogan, managed to defend the interests of the Turkish minority with careful moves and succeeded in restoring Muslim names, reopening the Turkish minority media and measures for the education of the Turkish minority. (168)

Despite the prohibitions of the 1991 Bulgarian Constitution, which forbade the creation of political parties with religious, racial or ethnic identity, the Movement took part in the parliamentary elections on 13 October 1991, after the Central Election Commission had decided that all the formations that had participated in the immediately preceding elections should take part in the elections and had judged that the Movement was not a political party. The Movement received 7.55% of the vote and 24 seats in the National Assembly. Also in the local government elections, which took place at the same time, the C.D.E. was successful in controlling local government in the areas where it was in the majority, such as in Kardzali district. (169)

Before and after the elections, Bulgarian MPs of the Bulgarian Socialist Party filed an appeal to the Constitutional Court, in the first case to ban the participation of the C.S.P. in the elections, and in the second case to annul the election of C.S.P. MPs, because in their opinion the C.S.P. was an ethno-religious party. The K.D.E. refuted these allegations and put forward the position that it was not an ethno-religious party and that its members were not only of Turkish origin and Muslims. The decision of the 12-member Constitutional Court had to be taken by a majority of 7 votes to accept the appeal and because one member of the Court had died during the proceedings, in the end the votes were 6 in favour of the appeal and 5 against, with the result that the appeal was dismissed and the C.D.E. was henceforth considered a legal party. (170)

Since then, the K.D.E. has participated freely in parliamentary and local elections. In the last parliamentary elections on 5 October 2014, it received 14.84% of the vote and 38 seats in the Bulgarian Parliament, making it the third political force in the country. (171) It also participates in the elections for the European Parliament and in May 2014 received 17.27% of the vote, electing 4 MEPs. (172)

3.1.3.3 Council of Europe findings on Bulgaria

Bulgaria, like all countries in Europe, continues to be inspected by the Council of Europe regarding the protection of minority rights.

The Council of Europe’s European Commission against Racism and Intolerance in its 5th report in 2014 notes progress in the criminal treatment of racially motivated homicide and bodily harm, as well as in the education of children from ethnic minorities, but makes recommendations for stronger criminal provisions against threats and public speech directed against minorities and is concerned about the action certain extremist groups and political parties in Bulgaria against Muslims and minorities, such as incidents of insults and violence against the Muslim community with threats and harassment against women in headscarves and against Muslim schools and mosques, the incidents on 20 May 2011 outside the Bania Bassi mosque in Sofia by supporters of the nationalist Ataka party and the November 2013 attack on a man from the Turkish minority. (173)

For the reported attack on the Bania Bashi mosque, the Supreme Mufti submitted a complaint to the European Court of Human Rights, which heard the case and in its decision of 24 February 2015 found a violation by Bulgaria of Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of the Council of Europe, which protects the right to freedom of religion, and sentenced the Bulgarian state to a fine. (174)

3.2 Factors that make the Turkish minority a state security problem

From the above articles (2 and 11) of the 1991 Constitution, it can be understood that the Bulgarian state addresses the issue of minorities and basically the Turkish minority, which is the largest, by prioritising state security, as it leaves no room for claiming territorial autonomy and separatist aspirations and does not even mention the term „minority“, but refers to citizens, whose individual rights it protects. However, it grants the Turkish minority the minority rights provided for in international conventions and declarations, which it has also incorporated into domestic law (Constitution and laws).

The Turkish nationality and the Muslim religion, which link the Turkish minority with Turkey, with which it maintains relations and which is still seen as a threat by Bulgaria, given its weighty historical past, due to the long Ottoman conquest and especially after Turkey’s military intervention in Cyprus in 1974, the military conflicts after the fall of the communist regimes in the countries of the former Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union and the recent events in Crimea and Eastern Ukraine are key factors leading the Bulgarian state to „secure“ the issue of the Turkish minority, which it sees as a threat to its security and territorial integrity.

The Bulgarian national consciousness, which had been formed before the liberation from Ottoman rule and the common characteristics of the Bulgarian nation (common origin, language and religion) determined the attitude of the Bulgarians towards the Muslim population that remained in the country after the independence of the Bulgarian state. In particular, the Turkish minority was seen by the Bulgarians as something foreign, as they did not speak the same language and were not Christians, but Muslims, and were seen as an Ottoman remnant and a threat to the security of the state, in contrast to the Pomaks, who were seen as something familiar, as they spoke the Bulgarian language. (175)

The ‚process of rebirth‘, as Zivkov’s 1985-1989 assimilation policy was called, was based on the view of some Bulgarian historians that a large part of the Turkish minority were descendants of Bulgarians who had been assimilated by the Ottoman conquerors after being forced to convert to the Islamic religion and speak the Turkish language. This policy of assimilation by Zhivkov had a decisive impact on both parties, the Bulgarian majority and the Turkish minority. The whole affair accelerated democratic processes in Bulgaria, as Bulgarians began to view minority issues with greater sensitivity and to see nationalism as a symbol of communist totalitarianism. (176)

According to research by Bulgarian experts who examined the behaviour and relations between Bulgarians and the Turkish minority, the

‚otherness‘ was known and accepted and each ethno-religious group saw the other as ‚foreign‘, and this was not natural and logical because of its particular characteristics. Thus the „Turks“ of the minority saw the Bulgarians as people who avoided hard work, and Bulgarians had the general impression that the ‚Turkish‘ minority were hard-working and had other skills, but also malicious and easy as people who avoided hard work, and Bulgarians had the general impression that the ‚Turkish‘ minority were hard-working and had other skills, but also malicious and easy to quarrel and conflict. Each group believed that at some point in the future relations between them could be exacerbated and saw the other group, in relation to the historical past, as ‚oppressors‘ and themselves as ‚victims‘. (177)

Over time, coexistence was strengthened by good neighbourly relations, the exchange of gifts on religious festivals (on the one hand, Bulgarians offered them red eggs at Easter, while the „Turks“ offered them sweets or lamb at Bayram), participation in family celebrations (such as marriage, baptism) and the maintenance of understanding relations between Christians and Muslims. Participation in these festivals and religious ceremonies shows the mutual trust and respect that prevails between them, which is a prerequisite for peaceful, conflict-free coexistence. (178)

Balkan scholars agree on the statement that religious and ethnic tolerance existed in Bulgarian society from the very beginning, after the liberation of the country from the Turks (1878). This attitude is explained by the fact that for centuries Bulgarians were accustomed to coexisting with other peoples of different languages and religions. Peaceful coexistence requires tolerance and this has always been the case except in times of war and political turmoil. Also, Bulgarians were never religiously fanatical in favour of Christianity and this facilitated tolerance towards the Muslim religion. (179) Relevant scientific research concluded that Bulgarians did not recognise political rights of minorities and only half of them accepted as a right of minorities to participate in politics and government with their own political schemes. That is why they were suspicious of the Movement for Rights and Freedoms, founded by Ahmed Dogan. (180)

Minority-majority relations in Bulgaria were determined by a special system of coexistence between Bulgarians and Turks, who over the centuries developed mechanisms to prevent conflicts at the local level, who sometimes overturn decisions of the central authority, which can endanger the inter-relationship. On the other hand, however, we should not overlook the existence of historical prejudices and fear of ethnic and religious minorities on the part of the majority, which is the cause of its negative attitude towards minority rights. (181)

Although the majority considers that strong ties within it are a source of security and protection, when these ties are found among minorities, combined with the specific characteristics of their way of life, such as the high birth rate and the geographical separation of their settlements, they are perceived by the majority as dangerous. (182) After Bulgaria’s accession to the EU, the majority wishes to acquire a „European identity“ and does not accept non-European characteristics. Religion and language determine the European or non-European characteristics and the „orientalism „183 that Western countries attribute to the Balkans is considered by Bulgarians to be caused and represented in Bulgaria by the Turkish minority. (184)

The conclusions of the research of Bulgarian experts from the International Centre for Minority Studies and Intercultural Relations confirmed the success of peaceful coexistence of Bulgarians and the Turkish minority, based on mutual understanding and tolerance. However, they also showed that there was hostility and negative predisposition towards the Turkish minority among a large part of Bulgarians and that they saw the Muslim religion as a factor in creating fanaticism within the minority. They also found that there were some negative factors that could lead to possible conflict in the future. These factors were the assimilation policy of the last Zivkov period (1984-1989), which had serious consequences and affected the attitude of the Turkish minority, and the economic crisis, which led to large-scale unemployment among the Turkish minority, who felt that unemployment was the result of unfair treatment by the state against them. Research showed that Bulgarians did not want the term minority to be mentioned because they felt that the term implied political aspirations and separatist ambitions and they feared a possible repetition of the events of 1974 in Cyprus with the Turkish invasion and occupation of the northern part of Cyprus under the pretext of protecting the Turkish community on the island. The old Bulgarian fears that the Turkish minority was a threat to the state and its territorial integrity, because it (minority) was heavily influenced by Turkey, still existed. (185)

From the beginning of the post-communist era, Bulgarians adopted the „Bulgarian National Model“ for the treatment of minorities, which excluded violence, in contrast to events in the former Yugoslavia, which included war violence and ethnic cleansing. The ‚Bulgarian National Model‘ recognised minority rights, but up to certain limits and within the single multi-ethnic and democratic society, and considered any aspiration to claim territorial autonomy and secession from any group to be forbidden and illegal. (186)

The Movement for Rights and Freedoms claimed to have played a crucial role in shaping this model. Indeed, the Movement never declared itself to be an ethnic movement, acted as a responsible political force, never spoke of territorial autonomy, and never sought to promote minority issues. (187)

Without ignoring the existence and influence of past prejudices and stereotypes about people belonging to a different ethnicity, post-communist Bulgaria avoided ethnic conflicts and the situation gradually improved. (188)

3.2.1 The influence of the Muslim religion (Islam) on relations between the Turkish minority and the Bulgarian state and society According to Simeon Evstatiev „The origin of the Muslim population dates back to the conquest of Bulgaria by the Ottoman Turks and is due to two factors, colonization by a Muslim population and the Islamization of the native population. The Muslims of the Bulgaria are divided into Turkish-speaking, Slavic-speaking and Roma. “ (189)

From the beginning of Bulgaria’s independent state (1878), the official religion, as proclaimed by the Bulgarians, was Orthodox Christian, but equal rights were granted to Bulgarian citizens who were members of other ethnic and religious groups. In practice, however, this was not implemented, as oppressive policies were often applied, aimed at homogenizing the state. In this context, changes in the names of members of minorities and settlements were also part of this policy, with the aim of eliminating the Ottoman heritage. The communist regime created great difficulties for Muslim communities, culminating in the assimilation policy of the Zhivkov government (1984-1989). (190)

Since the transition to a democratic regime, religious freedoms and rights of Muslims have been restored and the traditional administrative system of Muslim religious affairs, represented by the Supreme Mufti and his organs, responsible for the operation of mosques (mosques) and the administration of religious officials (hodjas and imams), has begun to function again. (191)

Initially, while the new government guaranteed the rights of religious denominations, public policy, projecting the secular character of the state, completely ignored them, especially Islam. This shows a suspicion of the Muslim minority. (192)

An important issue is the impact on relations between Bulgarian and Muslim society of international events related to Islam. Religious education, which is considered a private matter and not funded by the state, worsens rather than improves relations between the Christian and Muslim population, as it is cut off from the social and political life of the country. (193)

According to the 2011 census, Muslims number 577,139 people, of which 546,004 people declare themselves Sunni, 27,407 Shia and 3,727 simply Muslims, while the Turkish ethnic minority consists of 588,318 people. It is noteworthy that 21.8 per cent of the population did not answer the question on religion below. (194)