Introduction

Instances of breaches in civil and political rights have, in the course of the past year, undermined the degrees of national freedom globally. The Covid-19 pandemic has, most notably, contributed to exacerbating existing frictions and issues within political and societal environments. If, in comparison with other geopolitical areas, Europe displays a less concerning trend, the emergency has offered the right circumstances to enact measures that clash with values and principles of freedom, rule of law and human rights. These occurrences allow to create dangerous precedents for the whole region. The annual report by Freedom House on changing levels of freedom around the world provides an understanding of how, and to what extent, the health crisis has indirectly influenced an already precarious political atmosphere in several countries of Central-Eastern and South-Eastern Europe.

The Freedom in the World report

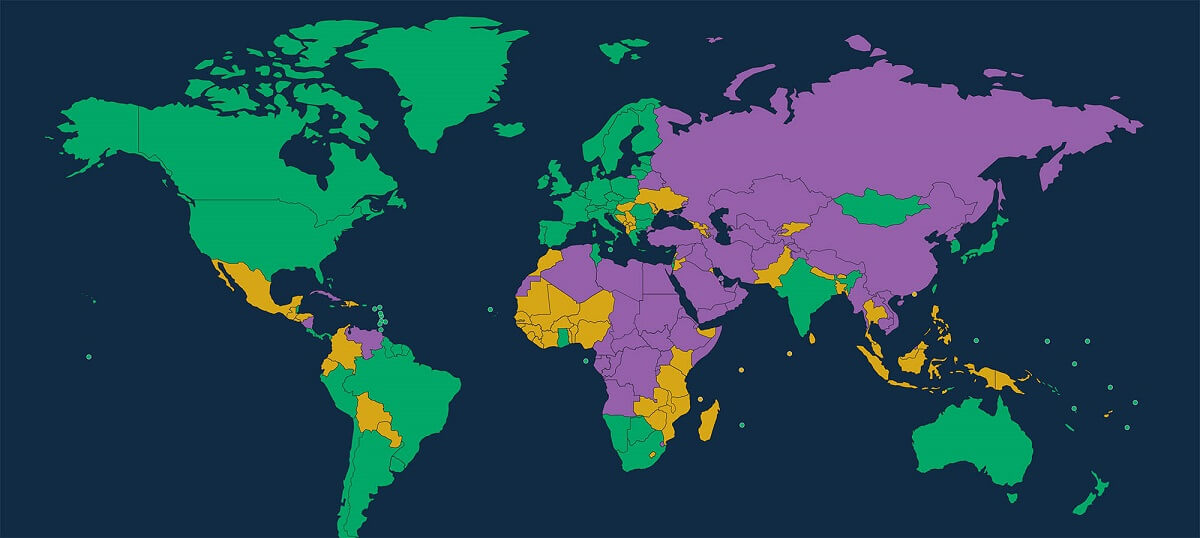

Since 1972, the non-governmental organization Freedom House publishes, on an annual basis, a report aimed at measuring and presenting variations in levels of freedom around the globe. Through the assignment of a score from 0 to 40, and from 0 to 60, respectively, Political Rights and Civil Liberties are evaluated in each country under scrutiny[1]. This year’s edition of Freedom in the World particularly addresses declined democratic values as an indirect consequence of the Covid-19 pandemic. The health emergency proved to be able to threaten civil rights and freedom in all geopolitical regions, while simultaneously shedding light on revived concerns and on further geographical areas. In the attempt to analyze in detail changing levels of global freedom, analysts focus on seven subcategories, namely electoral process, political pluralism and participation, functioning of government, freedom of expression and belief, associational and organizational rights, rule of law and personal autonomy and individual rights[2]. The scores awarded to the mentioned sub-topics allow for the classification of a country as “free”, “partly free” and “not free”[3].

A democratic emergency

In the course of the past year, governments all over the globe introduced sets of measures that, not rarely, proved to be incompatible with rule-of-law requirements, mainly in the name of the health crisis. At the same time, consequential civil protests and activist initiatives against local restraints were heavily punished. Indeed, the Covid-19 pandemic represented an unknown and uncontrollable threat. Therefore, it required effective and systemic restrictions, particularly in the first phase of the spreading of the disease, in order to firmly contain its diffusion among the population. Similar regulations, nonetheless, offered several political leaders the opportunity to further limit popular expression through controlling and limiting provisions.

Despite a steadily deteriorating trend, in terms of world freedom, evidenced in the past 15 years[4], the impact of the pandemic has proved to be significant in worsening already vulnerable conditions in geopolitical regions that are traditionally characterized by less stable political atmospheres. This year the highest number of “not free countries” since 2006 was, in fact, reached[5]. Nonetheless, new countries have come to the fore, as well, as demonstrative examples of democracy deterioration in the latest analysis.

A focus on Central-Eastern and South-Eastern Europe

A comparison between previous years’ reports of Freedom in the World and this year’s publication allows one to form an opinion over the countries that, in the past decades, have undergone the most decline in terms of local freedom and democratic rights. Three national entities located in Central-Eastern and South-Eastern Europe figure in the report among those countries that experienced the most intense worsening in levels of freedom in the past ten years. These are Hungary, Serbia and Poland[6].

Belarus

The 2021 report, however, places a strong focus on the events that occurred in Belarus, a country that is marked as “not free” in Freedom House’s inquiry. Flawed presidential elections taken place in August 2020 triggered a wave of protests directed at President Alyaksandr Lukashenka, leading to a consequent wave of violent responses through repression, arrest and torture. Despite a strong civilian attempt to overturn a regime that has been able to detain unconditional power for over 25 years, little is changed today in Belarus where, de facto, civil and political rights were suspended, in order to prevent further attempts to contrast the President’s rule[7]. Activists, representatives and leaders of movements aiming at promoting democracy and political dialogue in the country, including Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya and Veronika Tsepkalo, were prosecuted or forced to leave Belarus. In terms of the electoral process, Lukashenka’s re-appointment was the outcome of an unfair voting process, where, to mention one among several disputable instances, only 15 applicants out of 55 were accepted as candidates[8]. The voting procedure and Lukashenka’s election lacked the monitoring activities of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) and the subsequent recognition by the European Union. Political participation was, overall, highly and aggressively discouraged in Belarus in 2020, with strong reactions to hamper activism. Political opponents faced hard difficulties in their attempts to represent an alternative to Lukashenka’s regime, eventually risking serious threats to their safety. Although there is a strong popular request for a concrete democratic transition, the ruling government prevents any potential opportunity for it to occur. As far as the functioning of the government is concerned, the President practically concentrates on himself the totality of the branches of the government. Most importantly, the government’s actions lack transparency. The Covid-19 pandemic, indeed, exacerbated the dangers of potential unclear and unreliable information to citizens. Therefore, media concentration in the country has negatively contributed to the trend, due to extensive state control over mass media outlets and repression against independent sources of information. This all results in an almost non-existing rule of law[9].

Central Europe

As far as Hungary is concerned, its score declined by 21 points in the course of the past decade, and events that occured in 2020 reflect an existing trend in the political and social climate of the country.

In the most recent report, it is emphasized how the Fidesz-led government was able to obtain higher degrees of authority throughout the spreading of the Covid-19, by declaring the state of emergency immediately at the beginning of March 2020, and eventually prolonging it. The work by Freedom House highlights how this allowed for a greater range of movement to proceed with Viktor Orbán’s coherent plan in a variety of areas, overriding parliamentary approval. According to the report, the Hungarian performance has primarily deteriorated in the area of the functioning of the government, in comparison to the year 2019[10], due to repeated renewal of the state of emergency declared in March, eventually replaced by a state of medical emergency via the Health Care Act, in June, which gave analogous enhanced powers to the executive[11].

The Polish ruling party, Law and Justice (PiS), similarly exploited the emergency to put forward proposals that clashed with rule-of-law principles. As a fact, in April 2020, an attempt was made to change the electoral law to introduce a postal voting procedure aimed at proceeding with scheduled presidential elections, albeit circumventing the authority of the electoral commission[12]. The proposed mail voting procedure, eventually, failed to materialize, leading to regular voting in July and to the re-election of Andrzej Duda. However, the proposal raised high concerns, both nationally and internationally, on the legal basis of this abrupt initiative, which, moreover, put candidates from the political opposition in a condition of disadvantage, as unable to count on an electoral campaign during the pandemic[13]. In September 2020, the government’s plan to organize a postal election, although non-materialized, resulted in a ruling by a court in Warsaw declaring the unconstitutionality of the proposed voting procedure. In October 2020, a further measure sparked, in Poland, severe popular discontent. More precisely, the Polish Constitutional Tribunal ruled the unconstitutionality of abortion in relation to foetal defects, provoking massive popular protests. Nonetheless, the decision still entered into force in January of the current year, representing one among other rulings, such as anti-LGBTQ+ measures, whose implementation was hurriedly achieved in the course of the pandemic emergency.

Nevertheless, contrary to Hungary, Poland qualifies as a “free” country in the 2021 report. Orbán’s country, on the other hand, ranks among the “partly free” countries, with a score of 69 points on 100[14].

Western Balkans

The region shows different developments and trends. Albania successfully followed the indications by the OSCE to design electoral reforms through the role of a Political Council. However, due to the pandemic, freedom of assembly was neglected, with several instances of violent clashes between civilians and police officials throughout 2020[15]. Bosnia and Herzegovina has, in the past year, experienced a grown influence of opposition parties at the municipal elections, leading to increased political pluralism. However, issues such as transparency and corruption, as well as questions related to border management, remain evident in the country and have aggravated with the Covid-19 emergency[16]. North Macedonia has registered improvements in levels of freedom due to a better performance in the areas of the electoral process and the functioning of government, as a result of free and reliable parliamentary elections leading to a coalition government, between July and August 2020, and a more stable parliamentary atmosphere[17]. Both for Serbia[18] and Kosovo[19] freedom scores decreased by 2 points, due to amendments to the Serbian electoral law controversially introduced before the parliamentary elections, and due to an unconstitutional government established in Kosovo. Finally, Montenegro held, in August 2020, parliamentary elections that took place in a more ordinate climate, although not compensating for the country’s intrinsic problems[20].

Exceptions to a negative trend

Despite an overall exacerbation of democratic and freedom levels in the CEE region, several countries display positive and stable trends. As a matter of fact, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Greece, Latvia, Lithuania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Romania, are all categorized as “free” countries[21].

The Freedom in the World 2020[22] report, related to the year 2019, had underlined positive democratic changes in Ukraine, with President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, and in Moldova, with Prime Minister Maia Sandu. A slight increase in the score of Moldova was registered in the past year, despite the challenges caused by Covid-19. On the other hand, Ukraine’s performance has worsened. While improving in terms of transparency in the course of 2019, the progress made was canceled due to the annulment in October 2020, by the Constitutional Court, of laws against false declaration of assets. This event initially led to a constitutional crisis and concrete possibility, albeit averted, of dissolution of the Constitutional Court.

Nevertheless, both countries are still categorized as “partly free”.

Conclusions

The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered an unprecedented crisis that, starting from the health sector, has negatively influenced every aspect of society. In a similar climate, the points of conflict between national governments and already restless populations exacerbate. With a deteriorating social system, existing inequalities and discrimination worsened, and political abuses of power increased. Circumstances of emergency have led to weakened respect for political and civil rights, as a consequence of unpreparedness to face the crisis. On the other hand, the health emergency offered a number of leaders the opportunity to voluntarily pursue a plan aiming at undermining freedom and human rights at the national level. Simultaneously, however, the crisis, in a way, awakened manifestations of intense political participation and activism, dissent, rebellion, that collided with extraordinary acts of repression and constraints. A worsening of existing social, economic and political conditions has, oftentimes in the past year, prompted citizens to take action against the status quo.

Freedom House, through its analysis, underlines the need to safeguard democracy and freedom globally in times of crisis, in a united and international effort[23]. A focus should be put on the necessity to provide assistance for human rights and freedom defenders and punish anti-democratic instances to deter potential cases in the future.

The CEE region, particularly, is an area historically extremely politically vulnerable. Times of emergency, such as the pandemic, can once again trigger latent deficiencies and allow for leaders to exploit the circumstances. Nonetheless, previous crises demonstrate the innate resilience of democracy, when its values and principles are protected and upheld.

References

Freedom House. “Countries and Territories: global freedom scores.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

Freedom House. “FAQ – Freedom in the World.” Accessed June 7th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/faq-freedom-world#A1

Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2021, Democracy under Siege. New York: Freedom House, 2021.

Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2020, A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy. New York: Freedom House, 2020.

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Albania.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/albania/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Belarus.” Accessed June 7th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/belarus/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/bosnia-and-herzegovina/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Hungary.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2020: Hungary.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/freedom-world/2020

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Kosovo.” Accessed June 11th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/kosovo/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Montenegro.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/montenegro/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: North Macedonia.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/north-macedonia/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Poland” Accessed June 7h, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/freedom-world/2021

Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Serbia.” Accessed June 11th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia/freedom-world/2021

Tidey, Alice. “Poland’s all-postal presidential vote ‘dangerously undermines’ democracy, warns HRW.” Euronews. April 30th, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/28/poland-s-all-postal-presidential-vote-dangerously-undermines-democracy-warns-hrw

[1] Freedom House. “FAQ – Freedom in the World.” Accessed June 7th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/faq-freedom-world#A1

[2] Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2021, Democracy under Siege. (New York: Freedom House, 2021): p. 16

[3] Freedom House. “FAQ – Freedom in the World.” Accessed June 7th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/reports/freedom-world/faq-freedom-world#A1

[4] Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2021, Democracy under Siege. (New York: Freedom House, 2021): p. 1

[5] Ibid., p. 3

[6] Ibid., p.6

[7] Ibid., p.7

[8] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Belarus.” Accessed June 7th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/belarus/freedom-world/2021

[9] Ibid.

[10] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2020: Hungary.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/freedom-world/2020

[11] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Hungary.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/hungary/freedom-world/2021

[12] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Poland” Accessed June 7h, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/poland/freedom-world/2021

[13] Tidey, Alice. “Poland’s all-postal presidential vote ‘dangerously undermines’ democracy, warns HRW.” Euronews. April 30th, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/04/28/poland-s-all-postal-presidential-vote-dangerously-undermines-democracy-warns-hrw

[14] Freedom House. “Countries and Territories: global freedom scores.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

[15] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Albania.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/albania/freedom-world/2021

[16] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Bosnia and Herzegovina.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/bosnia-and-herzegovina/freedom-world/2021

[17] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: North Macedonia.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/north-macedonia/freedom-world/2021

[18] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Serbia.” Accessed June 11th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/serbia/freedom-world/2021

[19] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Kosovo.” Accessed June 11th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/kosovo/freedom-world/2021

[20] Freedom House. “Freedom in the World 2021: Montenegro.” Accessed June 9th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/country/montenegro/freedom-world/2021

[21] Freedom House. “Countries and Territories: global freedom scores.” Accessed June 8th, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/countries/freedom-world/scores

[22] Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2020, A Leaderless Struggle for Democracy. (New York: Freedom House, 2020): p. 23.

[23] Freedom House. Freedom in the World 2021, Democracy under Siege. (New York: Freedom House, 2021): p. 13-14