Cristina Jakob

The present work was elaborated and first presented in the course “A History of Latvian Culture: 20st century” teached by Edgars Engīzers at University of Latvia in Spring 2022

Download this contribution in PDF format here

Table of Content

- Money in Latvia before 1922

- Latvian Lats (1922-1940)

- Latvian Ruble (1992-1993)

- Latvian Lats (1993-2013)

- Euro (2014-today)

- Foreign currencies

- German Reichsmark (1941-1944)

- USSR Ruble (1940-1991)

I. Introduction

Money “represents national culture or deliberately blurs it”[1]. Banknotes and coins are multifaced objects representing a state. They can tell a lot about life in a country as well as its relation to power. It is therefore an interesting, unorthodox tool to investigate on the culture of a state and has even been used to measure institutional quality[2].

In the present work, it is assumed that money can give information about the government and the people simultaneously. In Latvia, especially the memory of the Latvian Lats is cherished[3]. Further, each regime change induced a change in currency, which means regular updates of the available data. Therefore, the present work will investigate on the link between currency and Latvian culture in the 20st century and answer following research question: What does money in Latvia indicate about identity, mentality, and state power?

To do so, the literature on money and identity as well as iconography is reviewed first. Then, the context is outlined and the currencies in time are described and analysed one per one. Thereby, the present work will focus on currencies of the Republic of Latvia as a sovereign state and, thus, only cursorily consider foreign currencies which were used during occupation times. Lastly, the limitations of the present work are discussed, and a conclusion is drawn. It is widely acknowledged in literature that money is a good way to study culture for several reasons. Firstly, it must be recognisable by featuring typical aspects and secondly, it is regularly updated which makes it particularly suitable for comparative studies[4]. Further, the relation between money and identity lacks scientific research and especially interdisciplinary works[5]. Therefore, the present work will focus in depth on the Latvian case. The aim is to give an alternative interpretation of political life in Latvia over the 20st century.

II. Literature

In this part, the scientific literature on the significance of money for identity and the dimensions of iconography will be reviewed. Thereby, a wider context can be established which will allow for interpretation of evolutions in Latvia in the next part.

1. Meaning of Money for Identity and state legitimization

Money is widely recognised as being a national symbol often aiming to glorify the current regime[6], which is sometimes called “banal nationalism”[7]. Even in a changing context of globalisation and digitalisation blurring former boarders, nations continue to affirm their identity through money[8]. When visiting a new country or doing business abroad, the currency even becomes a direct ambassador of the state[9]. Thus, the question on the represented identity and used tools to do so emerges.

National identity transmitted on banknotes and coins can be seen in two opposite ways. On one hand, these characteristics could be defined by leaders and preached to the society, whereas, on the other side, the leaders could embrace these characteristics, which have been created by society[10]. A state can reaffirm its legitimacy by highlighting common distinctive values justifying its existence. In other terms, the interaction between visual symbolism and construction of nations or legitimising states is a complex process[11]. Further, the expressed views also inform about the power relations within the state. Thiel[12] established that money can symbolise identity, power, foreign policy, and trust. Overall, banknotes and coins might give a good overview of what makes a country unique.

Not only the symbols on banknotes and coins but also their daily use influence state legitimization. When one uses a currency, this person is implicitly accepting the authority of the state and legitimizing its existence. In the opposite situation, when one uses a foreign currency on a daily basis within a country, this express mistrust towards the state and is an implicit questioning of its right to exist.[13]

Overall, it is established that money might be seen as a symbol for identity of a nation but also an indication about the organisation of state power in the country. In the next part, the literature about iconography of money will be outlined.

2. Iconography of Banknotes and Coins

When money emerged as a symbol of sovereign states in the 19th century, iconography, the visual features on money, became increasingly complex[14]. To understand how iconography might be interpreted, the production process must be understood.

The design and creation of banknotes and coins is a complicated process[15]. The first step is to define the general theme of the serie[16]. Then, a competition is carried out where several artists might submit their work, and which is evaluated later by a committee, but the final decision remains with the commission[17]. The committee and the commission usually are designated by the Central Bank which is strictly independent from the government[18].

One of the main drivers to initiate this process is the prevention of counterfeit[19]. There is constant research on how to keep money safe from illegal copies[20]. Further, decisions on the size and font style of the central information, namely the value and the issuing bank as well as the size distribution between the different entities limits the possibilities of the designer[21]. Therefore, the post-modernist statement that art is not limited to fine arts and inter alia includes money may be limited by these requirements[22].

Unwin and Hewitt focused on figures on banknotes in their analysis. Thereby, the human ability to recognise faces precisely and effectively was seen as a fraud protection and one reason why money is often featuring them[23]. The fact that only few women are displayed on banknotes and coins is due to a male bias in the decision process but also to the chosen topics, which are rulers, scientists, and artists, and often historically excludes women[24]. The absence of rulers of the 20st century on banknotes in Central and Eastern Europe is explained by the strive to represent more than the interest of a single party[25]. In light of part II.1. and the legitimization of states, the author of the present work argues that given the system changes in almost the whole region, featuring a ruler from a previous regime would jeopardise the essence of the current one. The focus on figures could be a specific bias in the case of the Latvian Lats[26].

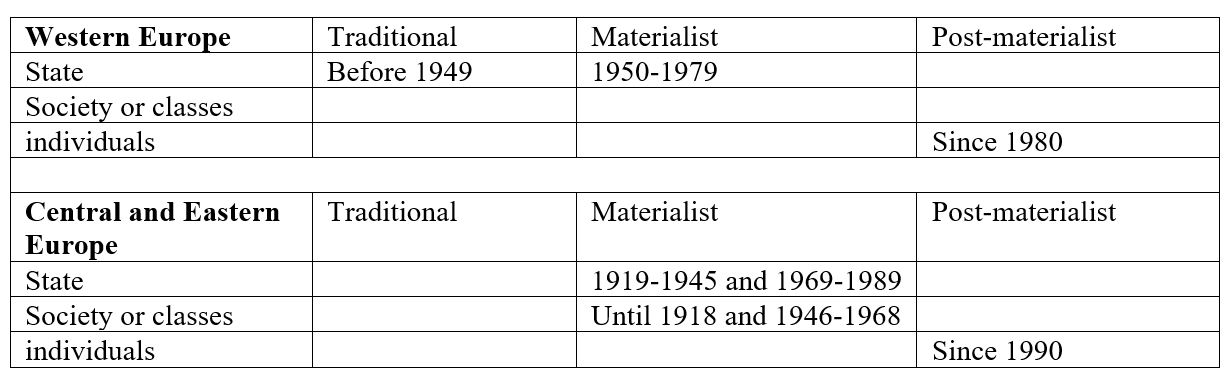

In trends in iconography are quite similar all over Europe. Hymans[27] established a matrix distinguishing between the categories traditional or materialist or post-materialist or non-state actor and state or society or identity (cf. Table 1). It was concluded that Central and Eastern European currencies reflect Western trends since the early 20st century, which might hint that identity is not only domestically formed and sourced but underlies some form of international anarchy of trends[28]. In other terms, money allows to investigate national specificities, but also international commonalities and European integration can be seen on banknotes in the fact that variations over time are significant but only small in different European countries[29]. For the present work, this implies that the evolution of Latvian currencies must be understood in a wider European context.

Table 1: Most common Categories of Iconography on Money in different time periods in Europe (own representation based on Hymans, 2004, P. 13-14 & 2010, P. 101-102)

Further, the effect of different factors has been analysed. Solely the difference between monarchies and republics that later does not display hereditary rulers on its money has proved to be significant[30]. Republics per definition do not have hereditary rulers and this result is therefore not surprising. Religion, dictatorship as well as the age of states did not have any measurable effect[31].

In research, different challenges have been identified to interpret monetary iconography. Already the colour specification can be difficult[32]. Symbols are even harder to interpret and sometimes can mean one thing and its opposite. For example, traditional motives can be seen as old-fashioned or a contemporary interpretation of heritage[33].

In conclusion, interpreting iconography is a difficult task. Iconography must be applied in combination with the interpretation of the producers and the public reception to find a complete narrative[34]. Especially the reception is difficult to predict[35]. Therefore, the present work relies on the information provided by the Central Bank of Latvia completed by information concerning the exchange rate, the pegged currency and the daily use. This will allow to address the critics address to the study of money iconography in literature. It is often assumed that the state decides on the design of money but in fact, this decision belongs to only a few people in a committee set up by Central Bank most of the time[36]. The role of state is thus contestable, and the production process should be taken into account. Further intentional and symptomatic meaning can differ[37].

III. Analysis

In previous part it was demonstrated that the analysis of money can be used to learn more about the culture of a state. This chapter is dedicated to the case of Latvia. The currencies will be analysed individually after a short outline of the context. Only the currencies of the Republic of Latvia as a sovereign state are considered in detail here. They are investigated in chronological order by taking a closer look on the iconography of banknotes and coins. This analysis will be completed by analysing the implemented exchange rates, pegged values and daily use as far as this data is available.

1. Money in Latvia before 1922

The present work focuses on the evolution of money in Latvia since 1922. At the begin of the 20st century and especially between 1918 and 1922, the main currency was the Russian Ruble but due to the conflict-situation German, Estonian, Russian, Bolshevik and own currencies created by cities circulated simultaneously[38]. Consequently, the period since 1922 was chosen for the analysis because starting from this point, one main currency could be identified for different time periods, which allows for building a coherent methodology as well as reaching useful and comparable results.

2. Latvian Lats (1922-1940)

The Latvian Lats was first introduced on the 3rd of August 1922 as first currency of the independent Republic Latvia proclaimed on the 18th of November 1918[39]. The Lats was pegged to the gold standard and one Lats must be exchanged for 0.2903226g of gold until 1931 when the world financial crisis occurred[40]. Later the time where the Lats was used is remembered as interwar golden age, symbolising the development of the Baltic states as modern nations[41].

There were at least three different designs of the Lats during this period, of which most were designed by Rihards Zariņš[42]. First, the new currency was printed over the old Ruble banknotes[43]. Later, the different series displayed different colour schemes and designs[44]. The Latvian Lats banknotes from the 1920s displayed female peasants, blazons, views, and men in costumes[45]. Thus, in the classification of table 1, these motives would be described as society and materialism as well as individuals and materialism. Thereby, the iconography of the Latvian Lats was ahead of the currencies of Latvia’s neighbours’ average. In the 1930s, the iconography became more complex, but similar motives were represented except that no non-state individuals appeared[46]. Thus, the Latvian Lats became more similar to the trends observed in other currencies in the region. This might indicate accrued cooperation with neighbouring states. It is also notable, that mostly agricultural work and human activity in a natural environment is represented: on one side this shows a close connection to nature but on the other side also a form of human dominance over the environment. The most often represented item was the coat of arms of Latvia, which indicates a strong sense of national pride[47].

The Latvian Lats coins evolved less over time, and it is notable that even though the font changed, the design of the figures on the current euro coins is very similar to the one of the Lats showing the folk maid, the coat of arms of Latvia but also lurk crowns and a peasant at work[48]. Further, unrealised projects displaying bread and food on a simple table give an indication about the value of simplicity in Latvian society at the time[49]. Daily life of peasants would here again have been represented as typical[50].

Especially the Folk Maid, also known as Milda, designed by Zariņš for the five lats coin is a famous “symbol of moral purity and dedicated work ethic”[51]. This idealised feminine figure in traditional costume is seen as one of the most interesting ones in Central and Eastern Europe[52]. Tradition and mentality of hard work are deeply linked in this iconography.

Overall, the Latvian Lats showed a strong orientation towards national agricultural heritage between 1922 and 1940. The sense of pride and uniqueness is further shown in the Latvian coat of arms and usage of only Latvian language. A quite interesting, unusual usage was made of coins by transforming them into ornaments and pendants first as sign of nationalism and later as discrete protest against occupation powers[53].

3. Latvian Ruble (1992-1993)

In the aftermath of the Soviet occupation from 1940 to 1991, an interim currency was established. The Latvian Ruble was first used in parallel to the USSR Ruble with an exchange rate 1:1 and became the only legal tender in July 1992 with a flexible exchange rate towards the Russian Ruble[54].

The Latvian Ruble banknotes featured no pictures but were very bright[55]. It appears clearly that a new currency was needed quickly and that security features prevailed over design. Thus, this currency can be interpreted as the need for a quick detachment of the former USSR but gives only little indication about Latvian culture, except, that it should be clearly distinguished from Soviet identity.

4. Latvian Lats (1993-2013)

The perhaps most informative and representative money for Latvian culture nowadays is the Latvian Lats established in 1993. Reforms of the 1990s in Central and Eastern Europe aimed to create new stable currencies by highlighting economic sovereignty[56]. Plans for an own currency were announced only one day after the declaration of independence, which shows how important this step was to reach self-determination and detachment from the former USSR[57]. Indeed, money is seen as an important tool for state building since it allows foreign trade and business relations[58]. More than satisfying only economic needs, these currencies reflected memories of identity as well as plans for maintaining independence based on uniqueness in future.

The golden standard of the Lats in the interwar period was seen as a symbol of past welfare and a motivation to establish an as valuable currency again, even though this assessment was a mix of facts and fiction satisfied by keeping exchange rates high and classifying them internationally as elite currencies[59]. By basing the Latvian Lats in 1993 on basis of memories of a glorious past, a strong symbol of qualification for independence and incentive for the population to reach this level again was set. The Latvian Lats was pegged to the SDR, a basket of international currencies considered as particularly stable, and later to the Euro, which also shows an evolution in international relations and a growing trust towards other states.

The iconography on banknotes was completely different from the Latvian Lats in the first half of the 20st century. A holy oak tree, a river landscape of the Daugava, traditional homesteads, an old sailing ship referring to Riga as a member of the Hanseatic League, the folk maid and the folklorist Krisjanis Barons were represented[60]. The colour scheme was chosen by technical limitations and logic implementing green for the tree and blue for the ship[61]. The colour scheme is nowadays represented in the different floors of the National Library, which shows the importance of the Latvian Lats as national symbol[62].

The coins on their side represented more abstract themes such as the sun and the day, water through a salmon and land through cows. Interestingly, animals did not appear at all on banknotes but were central motives for coins. Several commemorative editions displayed different other animals and symbols of luck. Those items were collected in the same way as stamps and again, jewellery was made from coins, which indicates that the Lats was more than an economic tool.[63]

In Latvia, figures on money were expressly avoided[64]. This can be seen as progressist but also as a rejection of Western-European understanding[65]. In the present work, the author argues that the Lats had a very progressive iconography because its need for international recognition and its geographical proximity with the West[66]. Further, history has shown that Latvia was extremely committed to reaching the targets and joining the EU and the Euro zone[67], which strongly indicates, that these values were not rejected but embraced. Further, as it will be described in the next part, the Euro banknotes do even more avoid figures than the Latvian Lats did in 1993. Here again, the Lats was ahead of its time in terms of design.

Overall, the Latvian Lats was highly symbolic for the identity, mentality, and independence of the country. Peasants’ life, nature, and hard work were represented as central on money and in life. Maybe, money thereby reflected the hopes Latvia had for its independent future. Furthermore, the unorthodox use of money as collection item shows that it was more than a tool. During the Euro crisis 2008-2012, it is notable that only left-wing parties, which traditional defended the rights of the Russian-speaking minority in Latvia, pled for sinking the exchange rate because currency was not a symbol to them[68].

5. Euro (2014-today)

As described above, the Latvian Lats was a strong symbol for the Latvian population and its economic achievements after regaining independence. Thus, the support for the introduction of the euro was especially low among the Latvian population but higher among Russian-speaking groups who emigrated during the Soviet period[69]. After the introduction of the Euro, money ceased to be part of national identity even though the images on coins remained almost unchanged[70].

The iconography of Euro banknotes does not feature any faces but doors, windows, and bridges symbolising openness and cooperation through architectural epochs according to the ECB and the designer[71]. In terms of design, they are children of their time promoting European integration and avoiding conflict[72]. The lack of discourse and debate around the iconography was sometimes perceived as inhuman and lack of democracy reflecting an artificially constructed identity, but this might should be reconsidered in view of the interpretation of European values[73].

Coins are more specific since one side is common and symbolising the supranational dimension of the currency whereas the other is specific to the different member states[74]. Some national sides of coins have indeed created conflicts as for example the representation of the Waterloo battle through Belgium triggered French discontent[75]. Many figures are chosen by the states and Latvia features the Folk Maid on its one- and two-euro coins in opposition to their unusual absence on banknotes[76].

Before Euro, money mostly indicated boundaries of sovereignty[77]. Now, some perceive the Euro in the Roman tradition of a whole European monetary system[78]. Nonetheless, some EU member states have not adopted Euro because of economic reasons and symbolic value of their currency[79]. In any cases, the Euro is unique for Latvia’s experience since it is the first currency which is shared with other states in a friendly environment acknowledging its sovereignty.

6. Foreign currencies

As the iconography of foreign currencies will per definition not give indications about Latvian identity and mentality, this part will quickly give an overview on the use made of it in daily life in Latvia and the sovereign power system through monetary policy in the 20st century.

7. German Reichsmark (1941-1944)

The German Reichsmark in form of occupation marks was introduced when the German army occupied the territory of Latvia. Ironically, while the German occupier praised frugal life and savings, the exchange rate 1:10 completely annihilated the savings of the Latvian population[80].

The population was reluctant to use this currency and when it became the only legal tender in German-occupied of Latvia, people started exchanging products rather than using money[81]. This shows a strong distrust from the Latvian population. Thus, the vicious German monetary policy and the avoidance of the Latvian population might be an illustration of a generally flawed relationship.

8. USSR Ruble (1940-1991)

In 1940, the USSR Ruble started circulating in parallel with the Latvian Lats with the exchange rate 1:1 and during the incorporation into the USSR, the Bank of Latvia was reorganised as office of the central bank of the USSR[82]. Even though Latvia had no sovereignty, this at least showed a will to integrate it in an economic frame.

Without surprise, the banknotes represented Soviet leaders as well as Russian cities[83] and the coins soviet symbols such as Moscow, sports, and the USSR coat of arms[84]. This theme of motives did not change with the monetary reform in 1961.

The use in the population became widespread and the institutionalisation within Latvia shows that there was not really an alternative to the use of USSR Rubles. The absence of any regional specificities on the USSR money can be interpreted in light of the avoidance of general regional distinctions.

IV. Results

The previous part showed that currency in Latvia in the 20st century reflect its struggle for independence and self-determination. Thereby, it acknowledges that hard work of the people is needed to establish such a state. The most meaningful money for Latvian identity and mentality is the Lats, which tells a lot about Latvian life, roots, and dreams for self-determination.

The strong symbolic value of the Latvian Lats for the society is reflected in its unusual utilisation as collection item and raw material for jewellery as well as in its reference in national buildings such as the colour system in the National Library and Milda on top of the Independence Monument. It is particularly interesting that the iconography of the most important sovereign currency, the Latvian Lats, was clearly ahead of its time in whole Europe. In contrary, the rest of Central and Eastern Europe reflected Western trends with one to two decades delay[85].

Altogether, the Latvian Lats and Latvian money in general unifies Latvian society through its history but also through its aspirations for the future. In the same way, the peasant symbolic can be interpreted as historical roots but also as the contemporary importance of hard work. Foreign currency shows the power relations of occupiers with the Latvian society and are historical evidence for difficult relationships.

V. Discussion and Limitations

The present work shows an interesting perspective on Latvian history and culture through the lens of money. Nonetheless, it cannot be excluded, that central aspects are not represented in banknotes, coins, and monetary policy. Thus, the importance of public reception and the daily use of money is highlighted here again.

One specific challenge to the analysis of newer Latvian currencies is the absence of figures on banknotes since the 1990s, which are the most investigated tools for banknote analysis in literature[86]. Consequently, new interpretation methods and frameworks shall be established in the future to tackle nowadays challenges.

Further, as the present work has been written by a non-Latvian author, there remains a risk of misinterpretation despite all due diligence during research and interpretation. Generally, the present work therefore surely gives an interesting alternative to more classic tools but shall be interpreted in the wider context of Latvian and European history and society.

VI. Conclusion

In conclusion, money reflects the historical challenges of Latvia and its population through the 20st century. In consequence, the answers to the question about the implications of money for identity, mentality and state power are diverse. First, sovereign, and foreign currencies must be evaluated separately. On one hand, currencies emitted by an independent state reflect values of this country to some extent. On the other hand, foreign currencies indicate more about the relation between occupiers and the local population than about the people themselves. The Latvian Lats is the most representative currency for Latvian identity and mentality. Its focus on peasants’ life and agriculture reflects the hard-working society and its relation to nature which is rooted in the historical rural context. The Latvian Ruble was established quickly and shows a strong will for self-determination in the same ways as the Latvian Lats. On the other side, the German Reichsmark and the USSR Ruble as well as the policies associated to them illustrate the flawed relations between the occupying power and the Latvian population. Interestingly, the Euro can be qualified as a sovereign currency but is not seen as entirely part of identity. This might change and evolve with time and ongoing European integration. First and Sheffi stated that “As a symbol, banknotes help to maintain the nation-state’s borders in an age of de-territorialisation”[87]. In the case of Latvia and the Euro this might not apply but the national side of coins may become a symbol of Latvia within Europe in future. As physical money is not expected to disappear any time soon[88], the results of the present work can serve as inspiration for further studies and provide an alternative view on Latvian history and state power.

Bibliography

Bank of Latvia. (2022). Timeline. 100 Years for Latvia. Retrieved from: https://www.bank.lv/en/about-us/latvijas-banka-100

Beņķe, L. (n.d.). Latvian National Currency – the Lats. Architecture and Design. Retrieved from https://kulturaskanons.lv/en/archive/latvijas-nauda/

Duncmane, K., & Vēciņš, Ē. (1995). Nauda Latvjia: Latvijas Banka.

Eihmanis, E. (2018). Cherry-picking external constraints: Latvia and EU economic governance, 2008-2014. Journal of European public policy, 25(2), 231-249. doi:10.1080/13501763.2017.1363267

First, A., & Sheffi, N. a. (2015). Borders and banknotes: the national perspective. Nations and nationalism, 21(2), 330-347. doi:10.1111/nana.12097

Gilbert, E., & Helleiner, E. (1999). Nation-states and money : the past, present and future of national currencies. London: New York.

Gottfried, G. (2011). Aesthetics and Political Iconography of Money. In Pictural Cultures and Political Iconographies (P. 419-428). Berlin, New York: DE GRUYTER.

Han, M., & Kim, J. (2019). Joint Banknote Recognition and Counterfeit Detection Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 19(16), 3607. doi:10.3390/s19163607

Hartmann, S. (2018). Die Zukunft der Visualität des Bargelds, oder: Auslaufmodell Banknote? In Die Zukunft des Bargeldes (P. 167-183). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.

Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), 5-31. doi:10.1177/1354066104040567

Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 97-108. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2010.01.010

Jakob, C. (2022). Integration of Latvia in the Economic and Structural Policy of the EU. Forum für Mittelost- und Südosteuropa. Retrieved from: https://www.fomoso.org/en/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Latvia-in-the-Economic-and-Structural-Policy-of-the-EU.pdf

Langwasser, K. (2014). Designing New Zealand’s new banknote series. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin, 77(7).

Latvia to introduce own currency; Economists tout plan as `a concrete step to independence’; EAST BLOC: Final Edition. (1990). Edmonton journal.

Latvian Public Broadcasting, L. P. (Producer). (2020). Video: The story of Latvia’s “Lats” currency. Retrieved from: https://eng.lsm.lv/article/features/features/video-the-story-of-latvias-lats-currency.a351355/

Lawson, K. (2019). Using currency iconography to measure institutional quality. The Quarterly review of economics and finance, 72, 73-79. doi:10.1016/j.qref.2018.10.006

Lembke, B. (1922). Die neue lettische Währung. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 18, 116-118.

Norkus, Z. (2018). The glory and demise of monetary nationalism in the post‐communist Baltic states. Nations and nationalism, 24(4), 871-892. doi:10.1111/nana.12404

Penrose, J. (2011). Designing the nation. Banknotes, banal nationalism and alternative conceptions of the state. Political geography, 30(8), 429-440. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2011.09.007

Repse, E. (1993). “Be ready to be blamed for everything”: how Latvia introduced its currency. Finance & development, 30(4), 28-30.

Sassatelli, M. (2017). ‘Europe in your Pocket’: narratives of identity in euro iconography. Journal of contemporary European studies, 25(3), 354-366. doi:10.1080/14782804.2017.1348338

Thiel, C. (2013). Der Schöne Schein: Banknoten Als Untersuchungsgegenstand Einer Visuellen Soziologie. In (pp. 191-216): Soziale Welt.

Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), 1005-1028. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00042-7

——

[1] First, A., & Sheffi, N. a. (2015). Borders and banknotes: the national perspective. Nations and nationalism, 21(2), P. 331.

[2] Lawson, K. (2019). Using currency iconography to measure institutional quality. The Quarterly review of economics and finance, 72, P. 73-79.

[3] Latvian Public Broadcasting, L. P. (Producer). (2020). Video: The story of Latvia’s “Lats” currency.

[4] Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), P. 7.

[5] Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1006-1007.

[6] Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 97.

[7] First & Sheffi, 2015, P. 330

[8] Gilbert, E., & Helleiner, E. (1999). Nation-states and money : the past, present and future of national currencies. London: New York.

[9] First & Sheffi, 2015, P. 333

[10] Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), P. 5-6.

[11] Penrose, J. (2011). Designing the nation. Banknotes, banal nationalism and alternative conceptions of the state. Political geography, 30(8), P. 429.

[12] Thiel, C. (2013). Der Schöne Schein: Banknoten Als Untersuchungsgegenstand Einer Visuellen Soziologie. In (P. 206-210): Soziale Welt.

[13] Penrose, 2011, P. 429

[14] First, A., & Sheffi, N. a. (2015). Borders and banknotes: the national perspective. Nations and nationalism, 21(2), P. 334. & Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1007.

[15] Langwasser, K. (2014). Designing New Zealand’s new banknote series. Reserve Bank of New Zealand Bulletin, 77(7).

[16] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1015

[17] Penrose, 2011, P. 432

[18] Penrose, 2011, P. 438

[19] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1013 & Penrose, 2011, P. 432.

[20] Cf. Han, M., & Kim, J. (2019). Joint Banknote Recognition and Counterfeit Detection Using Explainable Artificial Intelligence. Sensors (Basel, Switzerland), 19(16)

[21] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1012-1013

[22] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1007. & Gottfried, G. (2011). Aesthetics and Political Iconography of Money. In Pictural Cultures and Political Iconographies (P. 419). Berlin, New York: DE GRUYTER.

[23] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1013

[24] Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1021-1023.

[25] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1018

[26] Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 100.

[27] Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), P. 10. & Hymans, 2010

[28] Hymans, 2010, P. 99

[29] Hymans, 2004 & Hymans, 2010

[30] Hymans, 2004, P. 17

[31] Hymans, 2004, P. 16-17

[32] Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1011.

[33] Hymans, 2004, P. 18

[34] Sassatelli, M. (2017). ‘Europe in your Pocket’: narratives of identity in euro iconography. Journal of contemporary European studies, 25(3), P. 355.

[35] Thiel, C. (2013). Der Schöne Schein: Banknoten Als Untersuchungsgegenstand Einer Visuellen Soziologie. In (P. 205): Soziale Welt.

[36] Penrose, J. (2011). Designing the nation. Banknotes, banal nationalism and alternative conceptions of the state. Political geography, 30(8), P. 432.

[37] Gottfried, G. (2011). Aesthetics and Political Iconography of Money. In Pictural Cultures and Political Iconographies (P. 419-428). Berlin, New York: DE GRUYTER.

[38] Duncmane, K., & Vēciņš, Ē. (1995). Nauda Latvjia: Latvijas Banka. P. 138-146 & 235-236.

[39] Bank of Latvia. (2022). Timeline. 100 Years for Latvia

[40] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 236. & Lembke, B. (1922). Die neue lettische Währung. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 18, 116-118.

[41] Norkus, Z. (2018). The glory and demise of monetary nationalism in the post‐communist Baltic states. Nations and nationalism, 24(4),P. 878.

[42] Beņķe, L. (n.d.). Latvian National Currency – the Lats. Architecture and Design.

[43] Duncmane, K., & Vēciņš, Ē. (1995). Nauda Latvjia: Latvijas Banka. P. 153-165

[44] Duncmane & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 154-158.

[45] Duncmane & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 154-157

[46] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 158-165

[47] Duncmane & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 153-165

[48] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 166-168

[49] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 170

[50] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 165-169

[51] Beņķe, n.d.

[52] Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1023.

[53] Latvian Public Broadcasting, L. P. (Producer). (2020). Video: The story of Latvia’s “Lats” currency. & Beņķe, n.d.

[54] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 237

[55] Duncmane, & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 218-221

[56] Unwin, T., & Hewitt, V. (2001). Banknotes and national identity in central and eastern Europe. Political geography, 20(8), P. 1007-1008.

[57] Latvia to introduce own currency; Economists tout plan as `a concrete step to independence’; EAST BLOC: Final Edition. (1990). Edmonton journal.

[58] Repse, E. (1993). “Be ready to be blamed for everything”: how Latvia introduced its currency. Finance & development, 30(4), 28-30.

[59] Norkus, Z. (2018). The glory and demise of monetary nationalism in the post‐communist Baltic states. Nations and nationalism, 24(4), P. 879-881.

[60] Beņķe, L. (n.d.). Latvian National Currency – the Lats. Architecture and Design. & Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1017

[61] Unwin, & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1020-1021

[62] Beņķe, n.d.

[63] Beņķe, n.d.& Duncmane, K., & Vēciņš, Ē. (1995). Nauda Latvjia: Latvijas Banka. P. 228-231.

[64] Unwin & Hewitt, 2001, P. 1015. & Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 101.

[65] Hymans, 2010, P. 107

[66] Hymans, 2010, P. 105

[67] Jakob, C. (2022). Integration of Latvia in the Economic and Structural Policy of the EU. Forum für Mittelost- und Südosteuropa.

[68] Norkus, Z. (2018). The glory and demise of monetary nationalism in the post‐communist Baltic states. Nations and nationalism, 24(4),P. 882.

[69] Eihmanis, E. (2018). Cherry-picking external constraints: Latvia and EU economic governance, 2008-2014. Journal of European public policy, 25(2), P. 232-237. & Norkus, 2018, P. 883

[70] Norkus, 2018, P. 884

[71] Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), P. 19. & Sassatelli, M. (2017). ‘Europe in your Pocket’: narratives of identity in euro iconography. Journal of contemporary European studies, 25(3), P. 358.

[72] Hymans, 2004, P. 20 & Sassatelli, 2017, P. 357

[73] Sassatelli, 2017, P. 359-360 & 363.

[74] Sassatelli, 2017, P. 356

[75] Sassatelli, 2017, P. 354

[76] Sassatelli, 2017, P. 356

[77] First, A., & Sheffi, N. a. (2015). Borders and banknotes: the national perspective. Nations and nationalism, 21(2), P. 330-331. doi:10.1111/nana.12097

[78] Sassatelli, 2017, P. 357

[79] First & Sheffi, 2015, P. 331

[80] Bank of Latvia. (2022). Timeline. 100 Years for Latvia.

[81] Bank of Latvia, 2022

[82] Duncmane, K., & Vēciņš, Ē. (1995). Nauda Latvjia: Latvijas Banka. P. 236-237.

[83] Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 102. & Duncmane & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 197-210.

[84] Duncmane & Vēciņš, 1995, P. 205 & 212

[85] Hymans, 2010, P. 97-108.

[86] Hymans, J. E. C. (2004). The Changing Color of Money: European Currency Iconography and Collective Identity. European journal of international relations, 10(1), P. 5-31. & Hymans, J. E. C. (2010). East is East, and West is West? Currency iconography as nation-branding in the wider Europe. Political geography, 29(2), P. 97-108.

[87] First, A., & Sheffi, N. a. (2015). Borders and banknotes: the national perspective. Nations and nationalism, 21(2), P. 332. doi:10.1111/nana.12097

[88] Hartmann, S. (2018). Die Zukunft der Visualität des Bargelds, oder: Auslaufmodell Banknote? In Die Zukunft des Bargeldes (P. 167-183). Wiesbaden: Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden.