Author: Maria Zilincikova

International students from Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) who study in Western countries were experiencing a strange dissonance in March. While their loved ones at home were taking home offices, stocking up on food and urging others to avoid social contacts, their universities still had mandatory attendance, cinemas were full and large scale events were taking place.

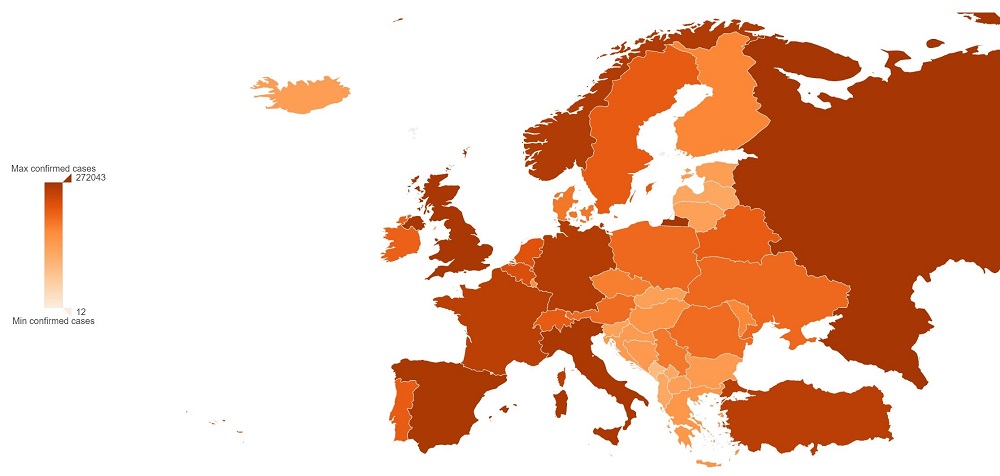

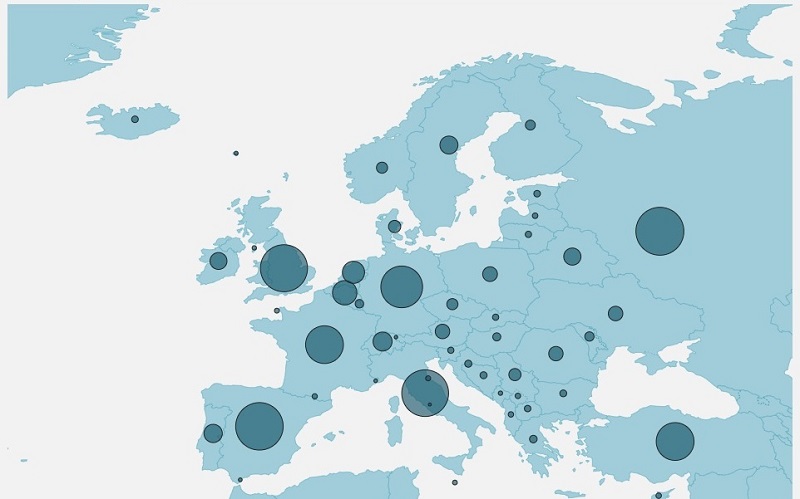

The consequences of this difference in approach between the countries in the West and in the East of Europe are becoming visible today. When looking at the map of coronavirus infections, as well as deaths due to the virus, a clear East-West divide emerges. It is worth exploring what different factors contributed to it.

Numbers of registered cases of infections. Source: BBC (1)

Numbers of deaths due to coronavirus. Source: BBC (1)

Each country has a different approach to tackling the various aspects of the crisis, and there are also differences in the way the statistics are reported. Contextual factors such as population density, demographics and movements of tourists and migrants need to be taken into account when comparing countries (2). However even when accounting for these differences, the difference in numbers is striking. It is thus necessary to examine differences in policy choices and public response in order to understand the differing results.

In the beginning, those news outlets which noticed the difference were warning of a lack of testing in CEE countries (3). Some were fearing that the peak in the East is only yet to come, others believed cases go underreported and a new Chernobyl is waiting behind the corner (4), (5).

However, as most countries passed their peaks and started the recovery, more attention was paid to the different policy approaches. Several news outlets noted especially Slovakia, as the country with the lowest death rate in the EU (6). Slovakia was praised for acting very quickly, and especially for encouraging public adoption of face masks through their use by political and media figures (7).

The debate on facemasks has been a heated one and it seems there is still not a conclusive answer. However, the literature that shaped the debate in the beginning emphasized the fact that facemasks can prevent transmission from patients who are not yet showing symptoms (8). While facemasks (especially home made) are not very effective in protecting you from contracting the virus, they can be a barrier in the spreading of respiratory droplets from you to others (9). As they are a good measure of source control, people are encouraged to use them to protect others from the danger they could themselves be (10).

While government appeals and media campaigns were for sure important in shaping the public image of face masks, individual grassroot behavior was also crucial. When taking a walk down the street in Slovakia, one could see face masks on dolls and signs such as „My mask protects you, your mask protects me.“ Masks can thus also be a cultural expression, a symbol of solidarity, reflecting a culture of cooperation and taking care of your fellow citizens (11), (12).

Let us take a step back and consider why this approach could be specific to CEE countries.

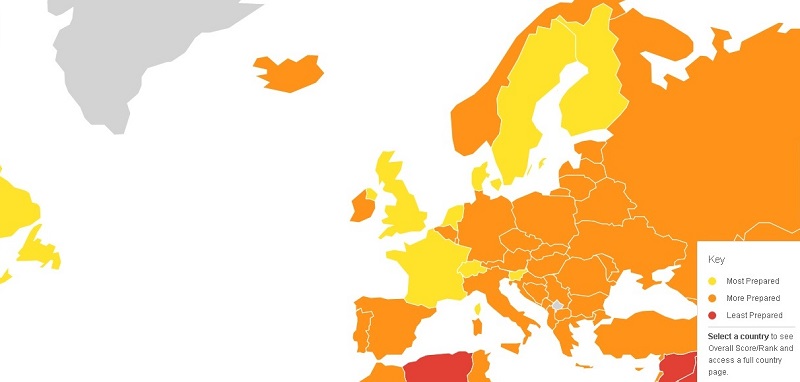

The Global Health Security Index (13) measures, among other things, how prepared are countries to respond to a pandemic:

Source: Global Health Security Index (13)

It is curious to see that some of the countries which were ranked as being most prepared, were also those which experienced the highest number of deaths, such as the UK, France or The Netherlands (14). On the contrary, the CEE countries were less prepared. This could explain the difference in policy choices. Especially the UK, Netherlands and Scandinavian states took a less restrictive and slower approach compared to CEE countries (15). The governments which know about the deficiencies of their health system can understandably be more inclined to respond to the pandemic very quickly, to mitigate potential catastrophic developments.

However it is not just the governments, which were quick to respond, but also ordinary citizens. Foreign Policy notes that the measures in Slovakia were so effective because of the compliance of the people (16). CEE countries have on average experienced a lower trust in institutions than Western states (17). In some countries, this has led to the phenomenon of „critical citizenship“ (18). People who reported lower trust in institutions were increasingly more politically active and were trying to take actions which would change the political situation they were dissatisfied with. Slovakia was among the countries experiencing this development.

Similarly to this finding, a research by students of Maastricht University compared the political engagement of international students from countries with varying levels of democracy. They found that students from countries with problems with rule of law and a low trust in the state had different perceptions of citizenship than those from fully functioning democracies. Students who distrusted their governments felt a duty to contribute towards making the situation better. They felt a loyalty to their fellow citizens and wanted to supplement the lack of state support by taking political action themselves (19).

The universal and uncontested use of facemasks in Slovakia and other CEE countries could be an expression of this perception of citizenship. Much like the universal compliance with regulations and following social distancing. While appeals for social distancing in order to flatten the curve were present everywhere, citizens who trust their institutions less and have experiences with structural problems of the healthcare system are arguably more likely to take such appeals seriously. Especially if the use of facemasks, and the compliance with other regulations, is seen as a way of protecting other citizens.

A crisis like the current one requires the commitment and solidarity of the entire population. The cultural context in the CEE countries could have made this factor stronger, and resulted in a strikingly lower death rate as compared to Western European countries. It is possible that since CEE governments come out of the crisis with fewer deaths than their western counterparts, it will lead the citizens to trust their governments in handling crises a bit more. But the collective action, home face mask manufacturing, and overwhelming support between the citizens will likely leave a significant mark for the future as well. Hopefully it can lead people to take a more active role in other areas of public life.

Sources:

- https://www.bbc.com/news/world-51235105

- https://www.bbc.com/news/52530918

- https://www.straitstimes.com/world/europe/coronavirus-eastern-europe-braces-itself-for-the-worst

- https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_coronavirus_in_eastern_europe_avoiding_another_chernobyl

- https://www.businessinsider.com/why-eastern-europe-fewer-coronavirus-cases-west-lift-lockdowns-2020-4

- https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-04-28/european-nation-with-least-virus-deaths-proves-speed-is-key

- https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/05/slovakia-mask-coronavirus-pandemic-success/611545/

- https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(20)30520-1/fulltext#%20

- https://erj.ersjournals.com/content/early/2020/04/27/13993003.01260-2020

- https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/using-face-masks-community-reducing-covid-19-transmission

- https://time.com/5815299/coronavirus-face-mask-ethics/

- https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/2020/04/coronavirus-america-face-mask-culture-changing-meaning-changes-too/

- https://www.ghsindex.org/

- https://www.statista.com/statistics/1111779/coronavirus-death-rate-europe-by-country/

- https://www.politico.eu/article/europes-coronavirus-lockdown-measures-compared/

- https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/05/06/slovakia-coronavirus-pandemic-public-trust-media/?preview_id=1005098&fbclid=IwAR08ON2_l8GPrtr6q7nakEo70tjR7weaHu9P_z7kn9YmXupgz2vjTV6bs4c

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/310005027_Does_Institutional_Trust_in_East_Central_Europe_Differ_from_Western_Europe

- https://www.europeandatajournalism.eu/eng/News/Data-news/From-low-trust-in-institutions-to-the-rise-of-critical-citizenship

- Horstmann,J., Kerolos, C. and Zilincikova, M. (2019). Still a voice to be heard: Transnational political participation and engagement among migrant students in Maastricht. Research project for Maastricht University. Unpublished.