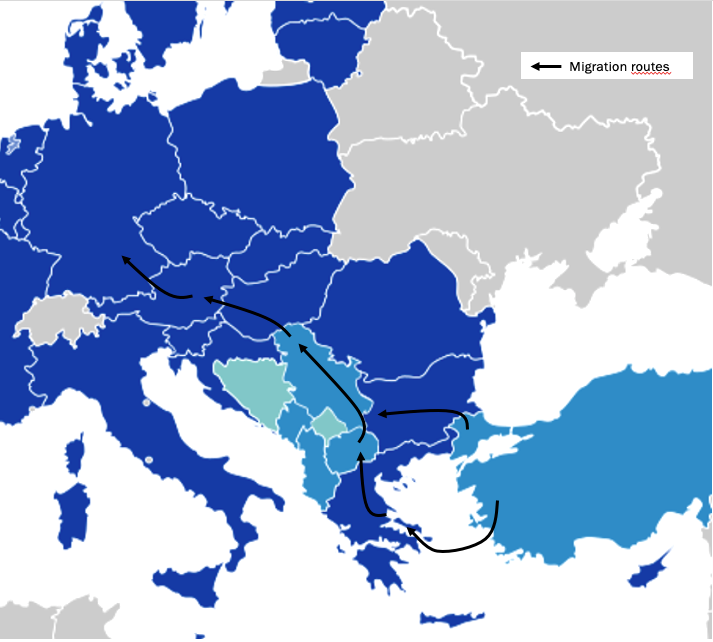

Every year, as winter approaches and temperature drop, there is once more a great deal of talk about the difficult situation of the migrants in refugee camps and in unauthorized tent cities in the Western Balkan. This time, news and controversy focused on the Lipa camp, on the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia, where the new Balkans Route leads. This way is chosen by migrants who wish to enter Europe because of its security as compared to the sea route.

The path taken is extremely complex, though: most of them are from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Syria, Iraq and Iran, they enter the European Union via Greece or Bulgaria and leave it for the Western Balkans [1]. But as well as Greece and Bulgaria, also North Macedonia, Serbia, Albania, Montenegro and Bosnia are just countries of transit, the real aim is to get into the Union through Croatia.

Although migratory phenomena on this route had already been registered in the nineties, since 2015 and with the deteriorating of the war in Syria, the Balkan Route became the main corridor on the ground to enter in Europe [2]. The enormous increase of immigrants and asylum-seekers between 2015 and 2016 caused the “European migrant crisis”: the European reception system, based on the Dublin Regulation [3], was unable to respond to such a large number of requests and collapsed on itself, leaving the burden on the Balkan countries.

At the beginning of this period, the corridor was equipped with the necessary structures to satisfy the basic needs: transit refugee camps, ad hoc train stations, food distribution centres and health clinics were built.

Figure 1: The Balkan Route

However, over time, the countries involved in the crossings began to feel overwhelmed by the exponential number of immigrants and by the inability of the EU to respond to asylum requests and started to close their borders: in April 2015, first of all, Bulgaria announced the extension of an existing wall on the Turkish border [4], then, in July, in Hungary, Orbán began constructing a fence between his country and Serbia, in addition, a new law made the illegal border crossing a criminal offence [5], a few months later, Hungary also declared its border with Croatia closed [6]. In November of that year, the Republic of North Macedonia built a metallic fence at the section of the border most used by refugee from Greece.

This closure created a terrible humanitarian crisis because many people remained blocked in Greece, which forced the country to create Idomeni refugee camp, later called “the jungle”.

Although these events had already exasperated a weak and unprepared system, what definitely changed the tide of those moving along the Balkan Road was the EU-Turkey Action Pact in March 2016. Among other things, it stated that Turkey would have taken “any necessary measures to prevent new sea or land routes for illegal migration opening from Turkey to the EU, and would have cooperated with neighbouring states as well as the EU to this effect” [7]. Moreover, “the European Union had begun disbursing the 3 billion euro of the Facility for Refugees in Turkey” [8].

This agreement meant the “official” closure of the Balkan Route and the blockage of thousands of immigrants in Greece and in the Balkan countries [9].

For some countries, the deal with Turkey “worked” and significantly reduced the number of new arrivals, in Germany, for example, in 2016 there were 280,000 asylum seekers, compared to 890,000 in 2015 [10]. According to Frontex (the European Border and Coast Guard Agency), illegal crossing on the Western Balkans route decreased from 130.320 in 2016 to 12.179 in 2017 [11].

Actually, this policy of border closures did not “de facto” close the route. Instead, the path followed just changed because people in transit started looking for more clandestine and therefore more dangerous routes to the EU. Between 2016 and 2017, Serbia became a major European hub.

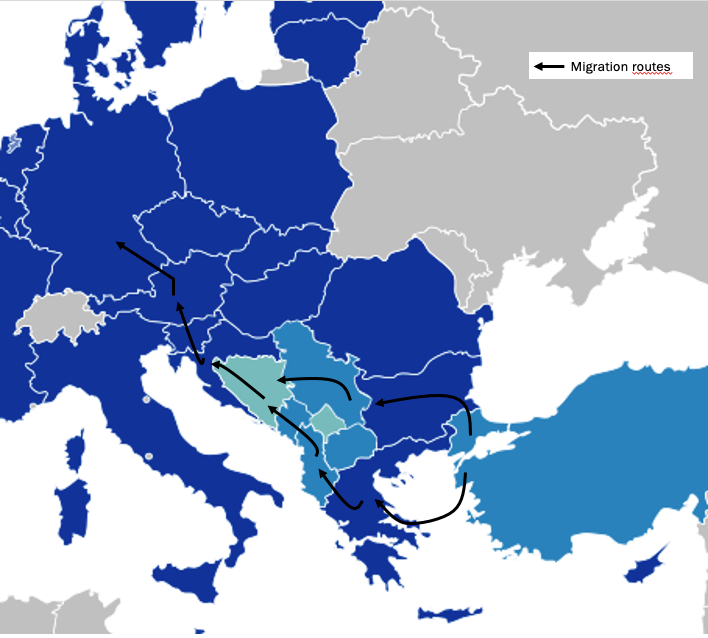

Figure 2: The Balkan Route after the fortification of borders

In March 2016, a total of 1700 refugees and migrants were stranded in Serbia. By the end of the year, their official number increased to 7.400, while the unofficial number was much higher [12].

In two years, the Serbian government has tripled the number of refugee camps in its territory, also thanks to the EU’s help that has financed in the country activities related to migration for a total of about 130 million of euro [13].

Those camps have always been overcrowded, especially after the completion of the wall between Hungary and Serbia in March 2017. At that time, the only legal way to get into Europe was to make an application to Hungary.

This country, not only was unable to receive more than 100 applications per day but also most of them were not accepted because the transit countries were considered “safe countries”. The number of applications considered by the Hungarian government dropped to nearly 10 per day [14]. Considering those strict conditions, many of the refugees tried “the game” [15].

With Hungarian migration policy becoming more restrictive and violence at the border caused by police reported, immigrants began to change course and opened a new way: it has shifted towards the south, crossing Albania, Montenegro, and then Bosnia, mainly arriving in Bihać and Velika Klanduša.

Figure 3: The main path followed today

Bosnia and Herzegovina was not even considered a transit country in early 2018, as indicated by the IOM report [16]. But, according to UNHCR, by the end of 2019, it was the country of the Western Balkan with the highest number of Asylum-seekers and refugees [17].

That country, as its neighbours, found itself completely unprepared to face an emergency like that. The European Union stepped in and since 2018 has paid to Bosnia approximately 50,2 million of euro to help the country in the management of migration flows [18]. Furthermore, under the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance, the special support measure in this field for Bosnia and Herzegovina was implemented by IOM in cooperation with UNHCR and UNICEF.

Like Serbia, in this territory, new refugee and transit centres have been created but often international press has reported their disastrous conditions. In addition to an already difficult situation, the fact that the state law is incomplete and that the cantons must decide on their individual territories only worsens the situation.

The status of the Lipa camp, 30 km from Bihać is paradigmatic of the general chaos of the country. It was born as a temporary centre, opened to address Covid-19 emergency and the declaration of the state of emergency.

Soon, the situation became unbearable and deteriorated, leading IOM to leave the camp because “for several reasons, mostly political, it never got connected to the main water or electricity supply, and was never winterized” [19].

While evacuating the camp, some tents caught fire and many refugees who had not settled in other camps found themselves in need. According to the most recent IOM report in February, 30 tents were installed to accommodate 900 migrants [20].

References:

[1] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/73832.pdf

[2] https://lungolarottabalcanica.wordpress.com/la-rotta-balcanica/

[3] Regulation (Eu) No 604/2013 Of The European Parliament And Of The Council establishing the criteria and mechanisms for determining the Member State responsible for examining an application for international protection lodged in one of the Member States by a third-country national or a stateless person, article 13 establishes that “an applicant has irregularly crossed the border into a Member State by land, sea or air having come from a third country, the Member State thus entered shall be responsible for examining the application for international protection. That responsibility shall cease 12 months after the date on which the irregular border crossing took place.”

[4] https://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/06/world/europe/bulgaria-puts-up-a-new-wall-but-this-one-keeps-people-out.html#

[5] https://www.internazionale.it/foto/2015/07/16/migranti-balcani-foto

[6] https://hungarytoday.hu/immigration-croatian-section-hungarys-anti-migrant-border-fence-completed-56088/

[7] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/

[8] https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2016/03/18/eu-turkey-statement/

[9] The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal and the Not Quite Closed Balkan Route, Bodo Weber, Dialog südosteuropa, June 2017

[10] https://www.internazionale.it/notizie/2017/01/11/nel-2016-in-germania-sono-calate-drasticamente-le-richieste-d-asilo

[11] https://frontex.europa.eu/along-eu-borders/migratory-routes/western-balkan-route/

[12] The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal and the Not Quite Closed Balkan Route, Bodo Weber, Dialog südosteuropa, June 2017

[13] https://movements-journal.org/issues/08.balkanroute/14.contenta–from-corridor-to-encampment.html#fn2

[14] The EU-Turkey Refugee Deal and the Not Quite Closed Balkan Route, Bodo Weber, Dialog südosteuropa, June 2017.

[15] Game” is a colloquial term established by migrants and refugees for an attempt at crossing the border https://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/serbia-games-of-violence-3.10.17.pdf

[16] https://rovienna.iom.int/sites/default/files/document/Flows_Compilation_Report_February_2018_%20%20%283%29.pdf

[17] https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/73832.pdf

[18] https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news_corner/news/eu-supports-bosnia-and-herzegovina-managing-migration-flows-additional-€20-million_en

[19] https://www.iom.int/news/thousands-migrants-forced-sleep-rough-after-closure-destruction-bosnia-camp

[20] https://bih.iom.int/sites/default/files/IOM%20BiH%20External%20Sitrep_05%2002%202021%20Final.pdf