Launched in 2012, the 16+1 sub-regional cooperation format brings together China and 16 central and eastern European countries (CEECs), consisting of 11 EU Member States (namely Hungary, Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, Croatia, Slovenia, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Latvia and Estonia) and five EU candidate countries (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia). These 16 CEE countries can serve as a bridgehead for exploring the European market. On the other hand, China is an attractive partner to these countries because of its growing economic power and willingness to invest heavily abroad. The Eurozone crisis highlighted the need to search for markets outside the EU and CEECs turned eastward.

The announcement of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013 further clarified China’s intentions towards the region. The 16+1 Initiative fits neatly into China’s larger foreign policy ambition to create an infrastructure network across Eurasia and Africa which would redirect trade flows to China. The CEE countries are obvious inclusions into this project due to their geographical standing.

The organization of the 16+1 cooperation does not allow the 16 countries to function as a regional bloc when dealing with China. Effectively, it creates 16 bilateral relations which are managed under a common strategy by Beijing. This leaves room for competition between these countries and it even encourages it, as the CEECs endeavor to prove themselves the best overall investment. It also allows China to sidestep the headache of having to deal with the EU as a bloc, which can leverage a bigger bargaining power than individual countries.

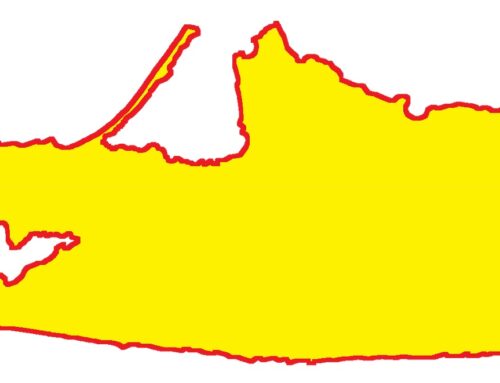

It is of little wonder then that the Initiative has raised some controversy in Western Europe, with Chinese investment seen as suspicious. The main worry is that Chinese money is a way to circumvent EU rules on such large-scale infrastructure projects. The EU investigation into Hungary following the Hungary-Serbia-China deal to build a railway connecting Budapest and Belgrade certainly confirms EU skepticism. The Commission is assessing the project’s financial viability and whether it has violated EU rules that require public tenders for large transport projects. The Budapest-Belgrade railway project is worth $2.98bn and 85 percent of the Hungarian share of the rail would be financed by a 20-year loan from China. This railway would be part of the Land Sea Express Route which links Chinese-owned port Piraeus in Greece with Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary and completes part of the European leg of the BRI.

It remains largely unclear what impact the 16+1 Initiative and the BRI have on the overall region. For the EU members involved, it is another bilateral relation that has the potential to result in large investments in their countries. Most of these investments remain, however, a potential, as the actual level of Chinese investment in CEECs is still lower than in Western Europe. It might be more fruitful to keep an eye on the 5 non-EU members involved, as pragmatism might lead them closer to China than comfortable. Unbeholden by tight EU legislation on public tenders and unaffected by the threat of infringement procedure, they might provide the real gateway for China into Europe and put a spoke in the wheel of long-term enlargement prospects for the EU.

Sources:

https://www.politico.eu/article/europes-new-eastern-bloc-china-economy-model-belt-road-initiative/

https://gbtimes.com/eu-probe-threatens-landmark-china-hungary-rail-project

Leave A Comment