Croatia lacks a foreign policy identity – the Western Balkan enlargement is an opportunity for change

After gaining its long-awaited independence and territorial integrity, Croatia set two major foreign policy goals: joining NATO and joining the European Union. It accomplished the first goal in 2009 under the government led by the Croatian Democratic Union (HDZ), and during the presidency of Stjepan Mesic. Four years later, the second goal was completed as well, with Croatia’s official accession to the EU in 2013. With both of its foreign policy goals accomplished, Croatia was left aimless on the international stage. Its foreign policy in the years following accession to the EU can be described as merely harmonizing stances with Brussels and Washington. The recent change in EU’s enlargement policy vis-à-vis the Western Balkans, resulting from the need to integrate the region for geopolitical reasons, offers an opportunity for Croatia to step into a new role – that of a leader in the Western Balkans, and a bridge to the EU. Croatia can accomplish this by directly engaging with the WB countries to serve as a mentor and aid them through the accession process, as the most recent country to complete it successfully itself.

Croatia shares a deep connection with the countries of the Western Balkans. It was part of the same state with 5 out of the 6 of them (Albania was the only one not part of the former Yugoslavia), and shares a similarity in languages and cultures. Neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina has a significant population of ethnic Croats, the majority of which live in the area directly bordering Croatia. This shared history, culture, and proximity are significant for two reasons. First, it is in Croatia’s national interest for the countries of the WB to be integrated in the European Union. Croatia would benefit economically through increased trade and investments in the region. Politically, it would benefit Croatia’s reputation in the region and in the EU to make the difficult process of enlargement smoother for both sides. However, the largest benefit to Croatia would come from a security aspect. Croatia has been protecting the European border since its accession to the EU (and for centuries before that) and has similarly to other borderland member states shouldered the brunt of the migration crisis affecting Europe. It has also suffered harsh criticisms from Brussels and other European capitals for its treatment of migrants reaching its border which has had a negative effect on its image. WB countries joining the EU would move the European border further east and alleviate nearly all of Croatia’s border issues. Second, due to the shared history, culture and other similarities, WB countries are dealing with similar issues on their accession path that Croatia dealt with a decade ago. Croatia is thus perfectly positioned to share its own experiences and expertise, and apply them to a context more similar to their own. This is an advantage that more developed countries with a longer democratic tradition do not have.

So, what is it exactly that Croatia can help with? There are several areas in which Croatia can offer support, including: administrative expertise, rule of law and judiciary reforms, economic competitiveness, sharing best practices, and promoting EU values. Furthermore, two main areas where Croatia can provide guidance are anti-corruption, border and customs management. It is somewhat ironic to recommend that Croatia give guidance on anti-corruption measures as the public is shaken by yet another major corruption scandal by a government minister, but despite its inability to entirely prevent it, Croatia has made major strides in battling corruption compared to its pre-EU membership days. Most notably, Croatia’s former prime minister Ivo Sanader is still serving a prison sentence for high-level corruption involving state-owned companies. Regarding border and customs management, Croatia is perfectly positioned to provide guidance and share experiences on how to assist the WB states in modernizing border management to meet Schengen requirements and facilitate trade. In 2010, Croatian Prime Minister Kosor gifted Bosnia and Herzegovina 160 000 pages of the acquis Communautaire translated into Croatian (one of Bosnia’s three official languages), thus saving Bosnia and Herzegovina major costs in time and resources required for such a large task. This is one example of how beneficial support of EU member states can be for aspiring members. There are other examples of member states acting as mentors for candidates. Germany played a major role in assisting Poland with carrying out the necessary reforms in the years prior to its joining the EU. Similar support was provided by the Nordic states to the Baltics, resulting in their accession in 2004.

Pursuing the foreign policy strategy outlined in this article would be relatively low-cost but carry a high reward for Croatia. It is also a strategy advocated for years by scholars and foreign policy experts. This begs the question – why have the Croatian foreign policymakers not pursued it?

The Croatian constitution splits foreign policy powers and responsibilities between the president and the prime minister. This framework requires a high degree of cooperation and coordination between the two offices in order to effectively plan and carry out foreign policy strategies. This has not been the case for quite some time. The current president Zoran Milanovic and prime minister Plenkovic have long moved away from simply not cooperating, and have instead been exchanging insults. Among the most recent foreign policy disagreements between the two leaders, Plenkovic accused the president of being pro-Russian and moving Croatia further from EU and NATO, in response to Milanovic’s opposition to Croatian soldier being dispatched on a NATO mission and possibly serving in Ukraine. President Milanovic has on the other hand criticized the prime minister for not involving him in discussions on opening new diplomatic and consular missions, and “simply expecting the orders to be signed” by the President’s office. The discord did not start with Zoran Milanovic’s presidency, however. Even the period from 2016 to 2020, during which both offices were occupied by an HDZ member, saw a disjointed foreign policy. President during that time was Kolinda Grabar Kitarovic, an HDZ candidate elected during the more radical right-wing leadership of Tomislav Karamarko. When more moderate and centrist Andrej Plenkovic took over as party leader and prime minister in 2016, the two often did not align on foreign policy issues. Plenkovic followed a staunchly pro-European policy, advocating for Croatia entering the Schengen zone, EU enlargement in the region, and implementing the Commission policies on development funds. Grabar Kitarovic on the other hand sought to align Croatia with US policy in the region, advocating for US protectionism and renouncement of global multilateral institutions – in line with Donald Trump’s policy during that time. Most importantly, her stance on Croatia’s policy in the region was that Croatia should continue to separate itself from the Western Balkans and instead deepen its ties with the countries of the Visegrad Group. When Milanovic was elected in 2019 many hoped that given his pro-European views, Croatia could finally have a more coordinated foreign policy. As these hopes did not materialize, the country still lacks a foreign policy identity. The upcoming presidential election set for the end of December presents a new opportunity for change.

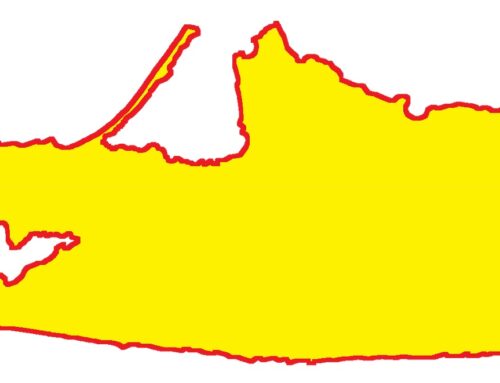

Picture: Freepik.com