Why has President Zelensky returned the renegade former Georgian President into Ukrainian politics?

Mikhail Saakashvili has once again returned to Ukrainian politics, this time on the back of the Presidency of Volodymyr Zelensky whose presidential bid Saakashvili supported. Zelensky appointed Saakashvili to head Ukraine’s National Reform Council after not finding enough support among his party to make Saakashvili the Deputy Prime Minister. Saakashvili’s role as coordinator of reforms is mostly advisory in nature and therefore not subject to a vote by the Ukrainian Rada (Parliament). Though Zelensky has avoided a possible crisis within his party by withdrawing his bid to make the Georgian ex-President deputy PM, he has placed the divisive figure back into the political spotlight.

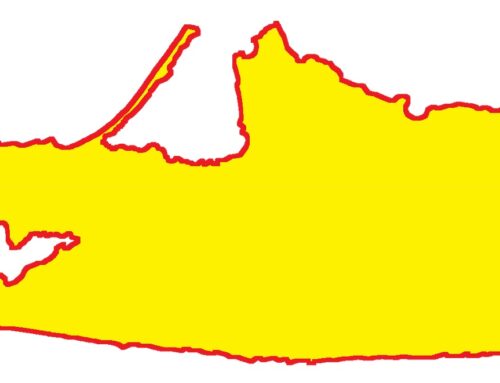

Having led one of the first “colour revolutions” in the post-Soviet space, Saakashvili ruled Georgia from 2003 for almost a decade. With a change in leadership in Tbilisi, Saakashvili was charged with several crimes and eventually sentenced in abstentia on charges of corruption and misuse of state power. He went into exile and continued participating in Georgian politics through his United National Movement (UNM) in which he remains a central figure to this day. Saakashvili re-launched his political career in Ukraine after the Maidan revolution in 2014 which he fervently supported. Having supported Poroshenko’s presidential bid, he was granted Ukrainian citizenship and appointed as governor of the port city of Odessa in 2015. Remarkably for a former President, Saakashvili gave up his Georgian citizenship in pursuit of his Ukrainian political career, one of the many shocking moves of this eccentric politician.

Saakashvili’s stint as governor did not last long, and in 2016 he resigned in protest at what he described as rampant corruption and oligarchic influence on government decisions. He formed his own party but soon found himself in government crosshairs. Poroshenko’s government stripped Saakashvili of his Ukrainian citizenship, leaving him de facto stateless, and ordered his deportation. Ukraine’s prosecutor then charged him with several crimes, including attempts at overthrowing the government. In chaotic scenes following his refusal to submit to arrest by a police commando, Saakashvili threatened to jump off an apartment building roof, scuffled with police and was freed from police custody by hundreds of his mobilized supporters. Ukrainian authorities eventually managed to deport Saakashvili, only for his supporters to help him force his way into Ukrainian territory. These bizarre and high-profile episodes have earned Saakashvili a notoriety well beyond the byzantine politics of Ukraine and Georgia.

The question then remains, why appoint Saakashvili to any government role given the politically combustible nature of his activities? Zelensky has given some answers to this mystery. Kyiv is currently negotiating an emergency loan programme from the IMF and needs to reassure creditors about the credibility of reforms being carried out. Saakashvili still enjoys a positive reputation among Western officials, and this could help negotiate better terms of any potential IMF loan. Saakashvili’s reformist credentials are further meant to signal Ukraine’s willingness to pursue structural reforms that have advanced little since the 2014 revolution. Yet beyond the official intentions of Zelensky’s government, Saakashvili’s appointment has repercussions beyond Ukraine’s borders. The Georgian government has been actively hostile to appointing the fugitive ex-president to any official role in Ukraine and in response to the recent nomination even recalled its ambassador from Kyiv. Though the shared interests of the two countries go beyond a single politician and will likely survive this recent upheaval, Saakashvili’s presence is unlikely to steer diplomatic relations in a positive direction.

The other unknown factor remains Russia’s reaction to a presence of a man who Putin once threatened to “hang by the balls” in the wake of the 2008 Russo-Georgian war. It is no secret that Putin and Kremlin officials have a deep personal dislike of Saakashvili, and his presence is unlikely to bring positive developments in bilateral relations as peace efforts in eastern Ukraine flounder. Initial improvements in implementing the Minsk agreement following Zelensky’s election, including the highly publicized prisoner exchanges, have been put on the backfooting as Zelensky faces a domestic nationalist backlash and decreasing popularity. Russian officials have so far refrained from commenting on Saakashvili’s appointment, having adopted a wait and see approach.

The lack of executive powers in Saakashvili’s newest function hasn’t stopped him from rapidly becoming one of the key media faces of Zelensky’s government. He gives frequent interviews, attends TV talk shows and is active on social media. Saakashvili’s presence further counterbalances the influence of interior minister Avakov, with the two men having a very public spat under Poroshenko’s presidency when Avakov first became interior minister. Intra-government power struggles might be just as important in Zelensky’s mind as relations with Western governments and domestic reforms. It remains to be seen what kind of change Saakashvili’s return will bring, and whether the promised reform drive of Zelensky’s government will finally take place.

References:

https://lenta.ru/articles/2020/05/15/mikho/

https://www.ft.com/content/8f163cc5-b7fe-4c78-b143-46c23a23048d

https://regnum.ru/news/polit/2951947.html

https://eurasia.expert/zachem-zelenskiy-vernul-saakashvili-v-ukrainskuyu-politiku/